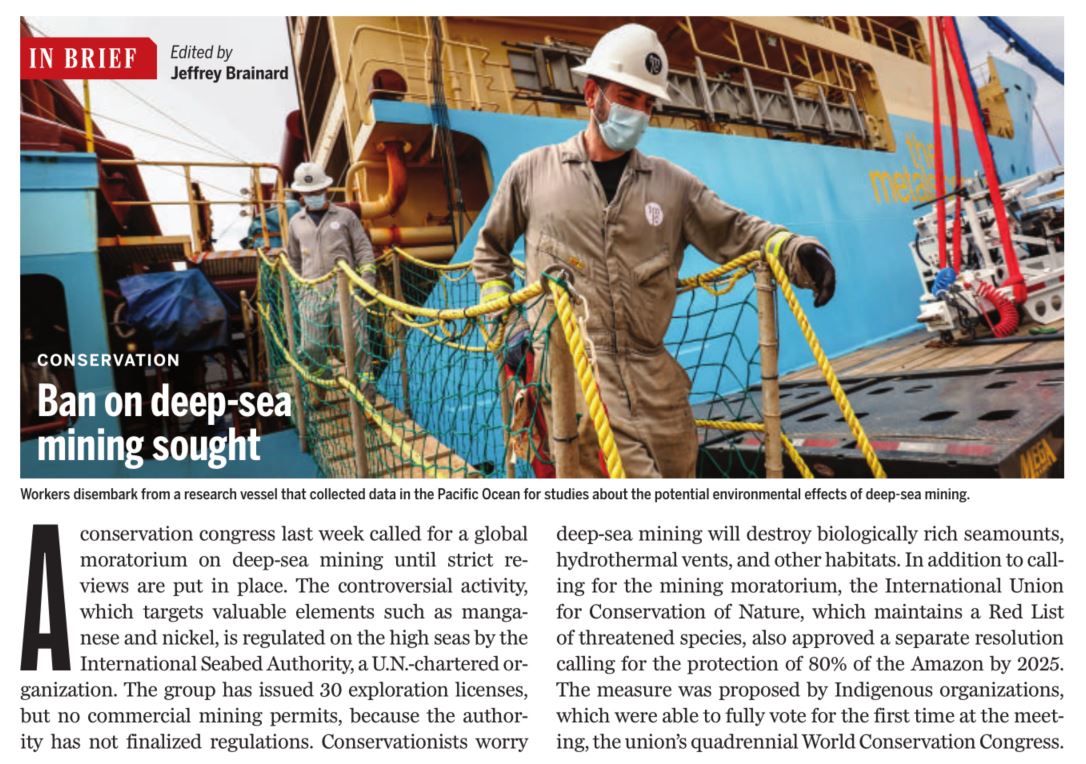

이번주 TIME지의 환경기사는 탄 감자 같은 물건의 사진으로 시작합니다.

이게 뭐지???

우리 눈엔 보이진 않지만

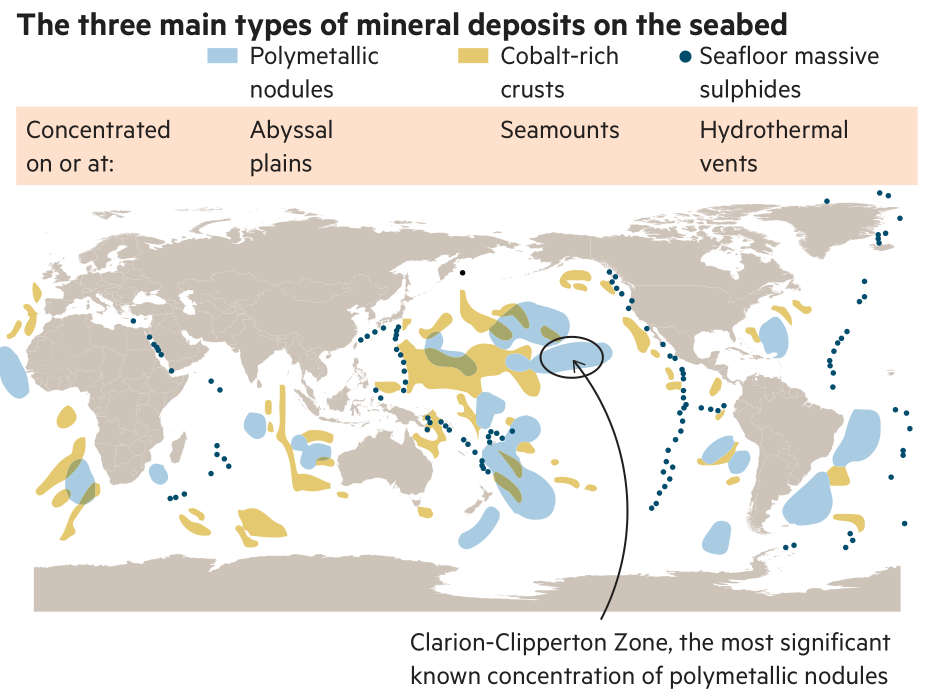

바다속 깊은 곳의 땅은 큰 규모의 금(fracture, 단열)이 있습니다.

위의 두개의 큰 단열 사이를 이렇게 부른다네요.

요기가 요즘 hot한가 봅니다.

"Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone"

최근 Hot한 바다속

벌써 세계 각국들이 치열한 경쟁을 벌이고 있었네요

물론, south Korea도 이 경쟁에 포함되어 있습니다.

Nodules - The Metals Company

The Metals Company plans to lift polymetallic nodules to the surface, take them to shore, and process them with near-zero solid waste, no tailings or deforestation, and with careful attention not to harm the integrity of the deep-ocean ecosystem. Our recov

metals.co

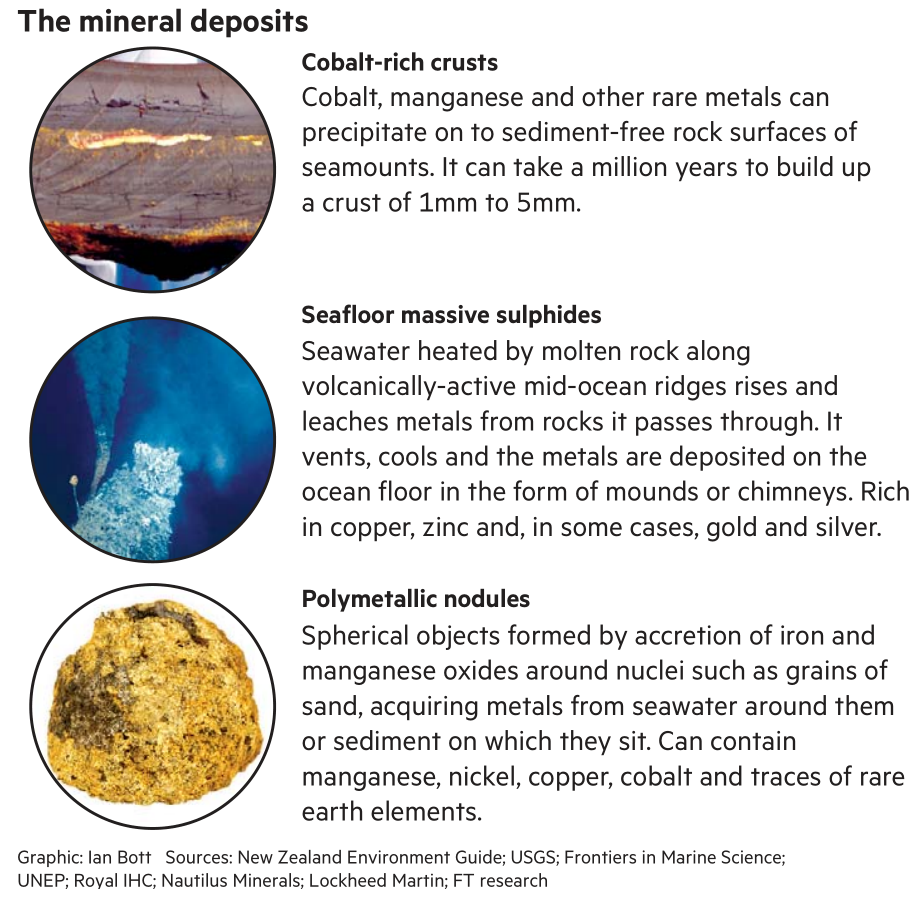

수류탄 처럼 생긴 이 물질의 정체는?

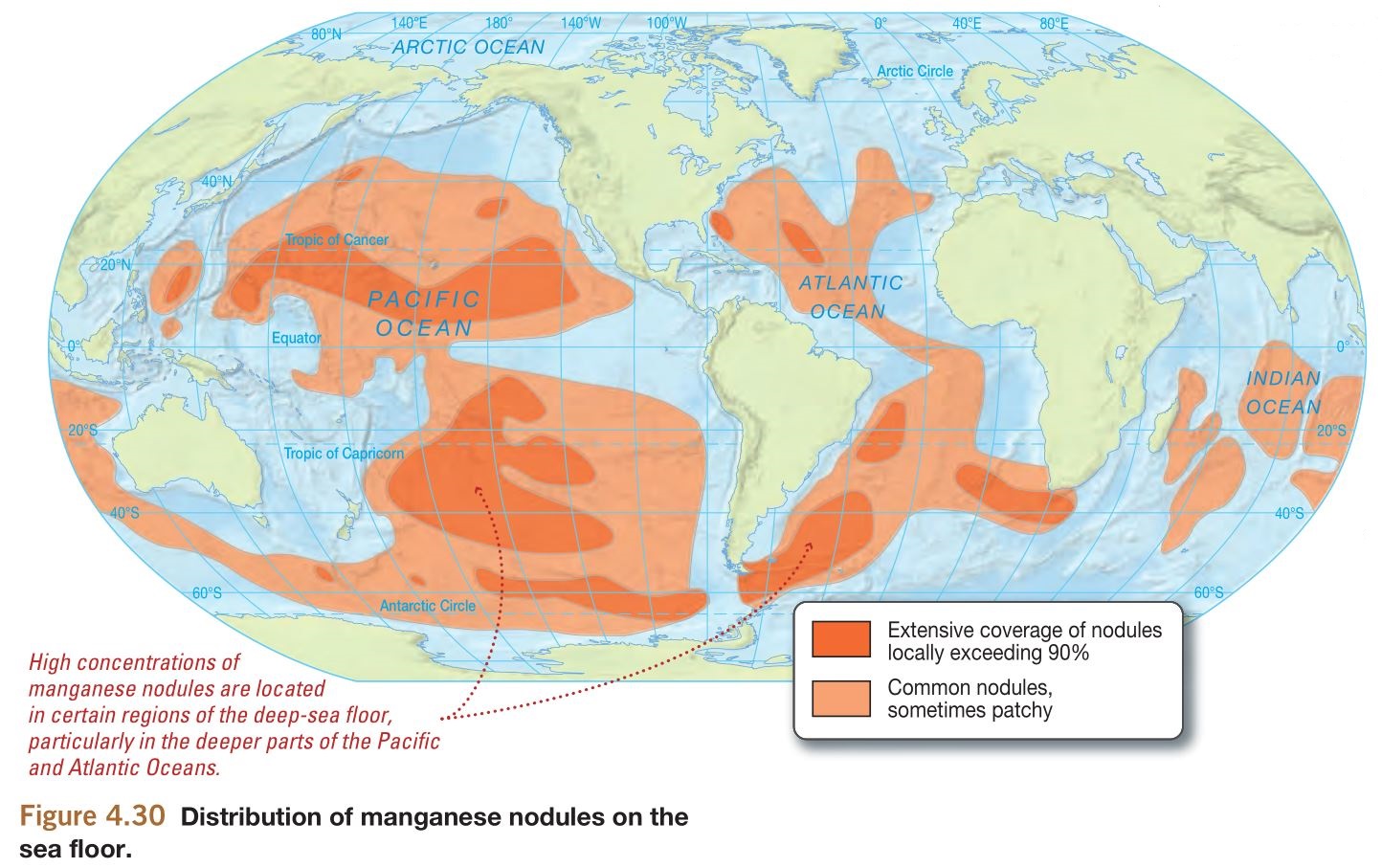

정식 명칭은 Polymetallic nodules인데

접두사를 보시면 짐작할 수 있듯이 '여러가지 금속질 물질이 포함된 덩어리'라고 볼 수 있습니다.

흔히 부르는 말로는 망간덩어리

망간 덩어리를 이루는 주요 금속으로는

코발트, 니켈, 구리, 망간 등이라고 합니다.

아니 구성물질들의 이름을 듣고보니

얘네들은 배터리를 만드는 데 필수적인 녀석들.

그렇습니다.

바다속의 수류탄은 배터리 생산에 꼭 필요한 재료가 됩니다.

그래서 태평양 한가운데서 여러 나라들이 코피를 튀기고 있는 것이죠.

망간 덩어리를 육상에서 코발트, 니켈을 추출하는 것보다 어떤 점에서 좋을까?

심해저 밑에서 금속질 물질이 뭉쳐져서 만들어진 물질이기 때문에 수류탄 덩어리의 99%가 이용가능하다는 점입니다.

보통 금속은 암석 속에 있어서 이걸 뽑아내려면 Tailing작업이 필요한데, 이게 필요없다는 것이죠.

그러니 채취 과정에서 환경오염이 거의 발생하지 않는다는 장점이 있습니다.

Tailing 댐이 뭔지 궁금하시다면

https://geowiki.tistory.com/1887

브라질 댐 붕괴는 기존 댐 붕괴와 무엇이 다른가?

오늘은 먼저 약간은 황당할 수 있는 이야기부터 시작하도록 하겠습니다. 다들 이런 짓(?)들 한번쯤을 해보셨겠죠? 손가락을 비틀어 '딱..딱..' 소리를 내는 그런데, 이 행위를 표현하는 단어가 있

geowiki.tistory.com

물론 심해저에서나 망간 덩이를 캐야해서 비용도 많이 들고

그 과정에서 CO2배출도 일어날테지만

이산화탄소 배출량은 육지에서 배터리 생산에 필요한 금속 광물을 채취하는 것에 비해 75%는 감소할 것이라고 합니다.

but,

형성 원리

DEEP-SEA MINING MAY SOON EASE THE WORLD’S BATTERY-METAL SHORTAGE

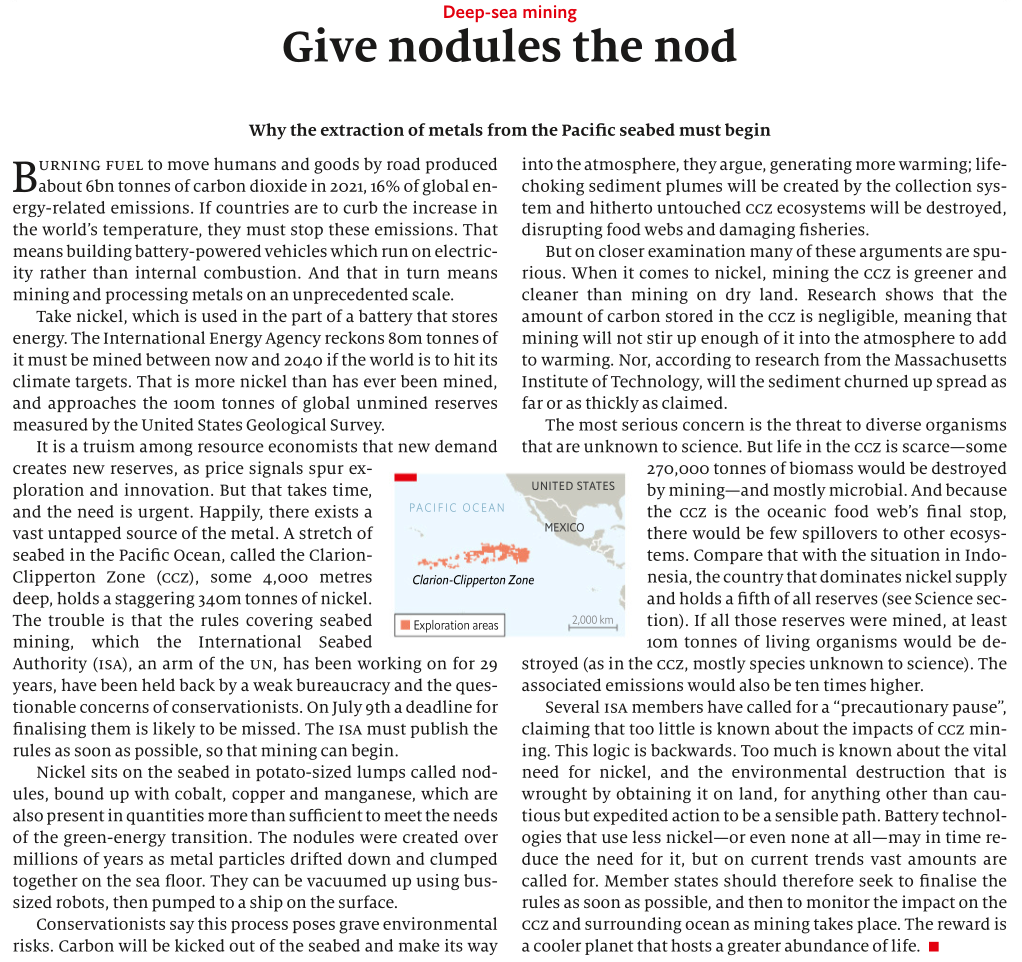

Pushed by the threat of climate change, rich countries are embarking on a grand electrification project. Britain, France and Norway, among others, plan to ban the sale of new internal-combustion cars. Even where bans are not on the statute books, electric-car sales are growing rapidly. Power grids are changing too, as wind turbines and solar panels displace fossil-fuelled power plants. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reckons the world will add as much renewable power in the coming five years as it did in the past 20.

All that means batteries, and lots of them—both to propel the cars and to store energy from intermittent renewable power stations. Demand for the minerals from which those batteries are made is soaring. Nickel in particular is in short supply. The element is used in the cathodes of high-quality electric-car batteries to boost capacity and cut weight. The IEA calculates that, if it is to meet its decarbonisation goals, the world will need to be producing 6.3m tonnes of nickel a year by 2040, roughly double what it managed in 2022. That adds up to some 80m tonnes of nickel in total between now and then.

Over the past five years most of the growth in demand has been met by Indonesia, which has been bulldozing rainforests to get at the ore beneath. In 2017 the country produced just 17% of the world’s nickel, according to CRU, a metals research firm. Today it is responsible for around half, or 1.6m tonnes a year, and that number is rising. CRU thinks Indonesia will account for 85% of production growth between now and 2027. Even so, that is unlikely to be enough to meet rising demand. And as Indonesian nickel production increases, it is expected to replace palm-oil production as the primary cause of deforestation in the country.

But there is an alternative. A patch of Pacific Ocean seabed called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is dotted with trillions of potato-sized lumps of nickel, cobalt, manganese and copper, all of which are of interest to battery-makers (see map). Collectively the nodules hold an estimated 340m tonnes of nickel alone—more than three times the United States Geological Survey’s estimate of the world’s land-based reserves. Companies have been keen to mine them for several years. With the coming expiry, on July 9th, of an international bureaucratic deadline, that prospect looks more likely than ever.

IT’S BETTER DOWN WHERE IT’S WETTER

That date marks two years since the island nation of Nauru, on behalf of a mining company it sponsors called The Metals Company (TMC), told the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an appendage of the United Nations, that it wanted to mine a part of the CCZ to which it has been granted access. That triggered a requirement for the ISA to complete rules on commercial use of the deposits. If those regulations are not ready by July 9th—and it seems they will not be—then the ISA is required to “consider and provisionally approve” TMC’s application. (The firm itself says it hopes to wait until rules can be agreed.)

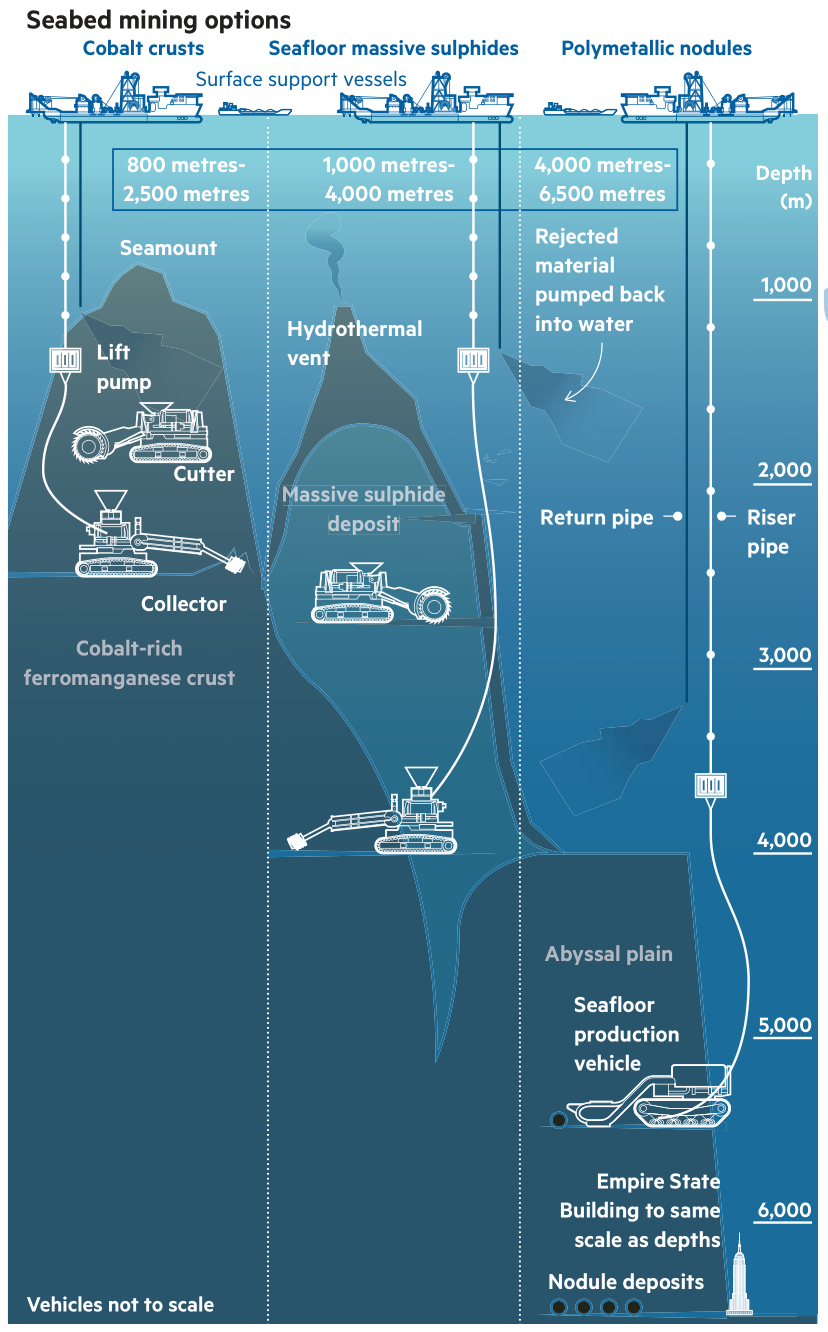

TMC’s plan is about as straightforward as underwater mining can be. Its first target is a patch of the CCZ called NORI-D, which covers about 2.5m hectares of ocean floor (an area about 20% bigger than Wales). Gerard Barron, TMC’s boss, estimates there are about 3.8m tonnes of nickel in the area. Since the nodules are simply sitting on the bottom of the ocean, the firm plans to send a large robot to the seabed to hoover them up. The gathered nodules will then be sucked up to a support ship on the surface through a high-tech pipe, similar to ones used in the oil-and-gas industry. Mr Barron says that his firm can break even on nodule collection at nickel prices as low as $6,000 per tonne; nickel currently sells for about $22,000 per tonne.

The support ship will wash off any sediment, then offload the nodules to a second ship which will ferry them back to shore for processing. The surplus sediment, meanwhile, will be released back into the sea at a depth of around 1,500 metres, far below most ocean life. And TMC is not the only firm interested. A Belgian firm called Global Sea Mineral Resources—a subsidiary of Deme, a dredging giant—is also keen, and has tested a sea-floor robot and riser system similar to TMC’s. Three Chinese firms—Beijing Pioneer, China Merchants and China Minmetals—are circling too, though they are reckoned to be further behind technologically.

As with mining on land, taking nickel from the sea will damage the surrounding ecosystem. Although the CCZ is deep, dark and cold, it is not lifeless. TMC’s robot will destroy many organisms it drives across, as well as any that live on the nodules it collects. It will also kick up plumes of sediment, some of which will drift onto nearby organisms and kill them (though research suggests the plumes tend not to rise more than two metres above the seabed).

Adrian Glover, a marine biologist at the Natural History Museum in London, points out that, because life evolved first in the oceans and only later moved to the land, the majority of the genetic diversity on the planet is still found underwater. Although the deep-ocean floor is dark and nutrient-poor, it nevertheless supports thousands of unique species. Most are microbes, but there are also worms, sponges and other invertebrates. The diversity of life is “very high”, says Dr Glover.

Yet in several respects, mining the seabed has a smaller environmental footprint than mining in Indonesia. The harsh deep-sea environment means that, although its inhabitants may be highly diverse, they are not very abundant. A paper published in _Nature_ in 2016 found that a given square metre of CCZ supports between one and two living organisms, weighing a couple of grams at most. A square metre of Indonesian rainforest, by contrast, contains about 30,000 grams of plant biomass alone, and plenty more if you weigh up primates, birds, reptiles and insects too.

But it is not enough to simply weigh the biomass in each ecosystem. The amount of nickel that can be produced per hectare is also relevant. The 2.5m hectares of seabed that TMC hopes to exploit is expected to yield about 3.8m tonnes of nickel, or about 1.5 tonnes per hectare.

Getting hard numbers for land-based mining is tricky, for the firms that do it are less transparent than those hoping to mine the seabed. But investigative reporting from the Pulitzer Centre, a non-profit media outlet, suggests each hectare of rainforest on Sulawesi, the Indonesian island at the centre of the country’s nickel industry, will produce around 675 tonnes of nickel. (One reason land deposits produce so much more nickel, despite the lower quality of the ore, is because the ore extends far beneath the surface, whereas nodules exist only on the seabed.)

All that makes a very rough comparison possible. Around 13 kilograms of biomass would be lost for every tonne of CCZ nickel mined. Each tonne mined on Sulawesi would destroy around 450kg of plants alone—plus an unknown amount of animal biomass, too.

PICK YOUR POISON

There are other environmental arguments in favour of mining the seabed. The nodules contain much higher concentrations of metal than deposits on land, which means less energy is required to process them. Peter Tom Jones, the director of the KU Leuven Institute for Sustainable Metals and Materials, in Belgium, reckons that processing the nodules will produce about 40% less greenhouse-gas emissions than those from terrestrial ore.

And because the nodules must be taken away for processing anyway, companies like TMC can be encouraged to choose places where energy comes with low emissions. Indonesian nickel ore, in contrast, is uneconomic unless it is processed near where it was mined. That almost always means using electricity from coal plants or diesel generators. Alex Laugharne, an analyst at CRU, reckons Indonesian nickel production emits about 60 tonnes of carbon dioxide for each tonne of nickel. An audit of TMC’s plans carried out by Benchmark Minerals Intelligence, a firm based in London, found that each tonne of nickel harvested from the seabed would produce about six tonnes of CO2.

In any case, metal collected from the seabed is unlikely to entirely replace that mined from the rainforest. Battery production is growing so fast that nickel will probably be dug up from wherever it can be found. But if the ocean nodules can be brought to market affordably, the sheer volume of metal available may start to ease the pressure on Indonesian forests. The arguments are unlikely to stay theoretical for long. Mr Barron of TMC aims to start producing nickel and other metals from the seabed by the end of next year. ■

_CORRECTION (JULY 6TH 2023): An earlier version of this piece said global nickel production would need to reach 48m tonnes per year by 2040, and would total 320m tonnes by 2040. The correct figures are 6.3m tonnes and 80m tonnes. Apologies for the error._

심해 채굴로 곧 전 세계의 배터리 금속 부족 문제를 해결할 수 있습니다.

기후 변화의 위협에 밀려 부유한 국가들은 대대적인 전기화 프로젝트에 착수하고 있습니다. 영국, 프랑스, 노르웨이 등에서는 내연기관 자동차의 신규 판매를 금지할 계획입니다. 법으로 금지하지 않는 곳에서도 전기차 판매는 빠르게 증가하고 있습니다. 풍력 터빈과 태양광 패널이 화석 연료 발전소를 대체하면서 전력망도 변화하고 있습니다. 국제에너지기구(IEA)는 향후 5년 동안 전 세계가 지난 20년 동안과 마찬가지로 많은 재생 전력을 추가할 것으로 예상합니다.

이는 자동차를 구동하고 간헐적인 재생 에너지 발전소의 에너지를 저장하기 위해 많은 양의 배터리가 필요하다는 것을 의미합니다. 이러한 배터리를 만드는 광물에 대한 수요가 급증하고 있습니다. 특히 니켈은 공급이 부족합니다. 니켈은 고품질 전기 자동차 배터리의 음극에 사용되어 용량을 늘리고 무게를 줄이는 데 사용됩니다. IEA는 탈탄소화 목표를 달성하려면 2040년까지 세계가 연간 630만 톤의 니켈을 생산해야 하며, 이는 2022년 생산량의 약 두 배에 달한다고 계산합니다. 이는 지금부터 그때까지 총 약 8천만 톤의 니켈을 추가하는 것입니다.

지난 5년 동안 수요 증가의 대부분은 열대우림을 불도저로 파헤쳐 광석을 채굴해온 인도네시아가 충족시켰습니다. 금속 연구 기관인 CRU에 따르면 2017년 인도네시아는 전 세계 니켈 생산량의 17%에 불과했습니다. 현재는 연간 약 절반인 160만 톤을 생산하고 있으며, 그 수치는 점점 증가하고 있습니다. CRU는 인도네시아가 지금부터 2027년까지 생산량 증가의 85%를 차지할 것으로 예상합니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 증가하는 수요를 충족하기에는 충분하지 않을 것입니다. 또한 인도네시아의 니켈 생산량이 증가함에 따라 인도네시아 삼림 벌채의 주요 원인인 팜유 생산을 대체할 것으로 예상됩니다.

하지만 대안이 있습니다. 클라리온-클리퍼톤 해구(CCZ)라고 불리는 태평양 해저에는 니켈, 코발트, 망간, 구리 등 수조 개의 감자 크기 덩어리가 산재해 있으며, 배터리 제조업체들이 관심을 갖고 있습니다(지도 참조). 니켈만 약 3억 4천만 톤이 매장되어 있는 것으로 추정되는데, 이는 미국 지질조사국이 추정한 전 세계 육상 매장량의 3배가 넘는 양입니다. 기업들은 지난 몇 년 동안 니켈 채굴에 열을 올리고 있습니다. 오는 7월 9일 국제 관료적 시한이 만료됨에 따라 그 어느 때보다 그 가능성이 높아 보입니다.

더 습한 곳이 더 좋습니다.

이 날짜는 섬나라 나우루가 후원하는 광산업체 더 메탈스 컴퍼니(TMC)를 대신하여 유엔 산하기관인 국제해저기구(ISA)에 CCZ의 일부에 대한 접근 권한을 부여받은 채굴을 원한다고 통보한 지 2년이 되는 날입니다. 이로 인해 ISA는 예금의 상업적 사용에 대한 규정을 완성해야 했습니다. 7월 9일까지 해당 규정이 준비되지 않는다면(준비되지 않을 것 같습니다) ISA는 TMC의 신청을 "검토하고 잠정적으로 승인"해야 합니다. (회사 자체는 규정이 합의될 때까지 기다리겠다고 밝혔습니다.)

TMC의 계획은 수중 채굴만큼이나 간단합니다. 첫 번째 목표는 약 2.5 헥타르의 해저(웨일즈보다 약 20% 더 넓은 면적)를 덮고 있는 NORI-D라는 CCZ 패치입니다. TMC의 사장인 제라드 배런은 이 지역에 약 380만 톤의 니켈이 매장되어 있을 것으로 추정합니다. 이 결절은 단순히 해저 바닥에 놓여 있기 때문에 회사는 대형 로봇을 해저로 보내 해저 결절을 끌어올릴 계획입니다. 그런 다음 수집된 결절은 석유 및 가스 산업에서 사용되는 것과 유사한 첨단 파이프를 통해 수면의 지원선으로 빨려 올라갈 것입니다. 배런은 현재 니켈이 톤당 약 22,000달러에 판매되고 있는 상황에서 톤당 6,000달러의 낮은 니켈 가격으로도 결절 수집을 통해 손익분기점을 맞출 수 있다고 말합니다.

지원 선박은 침전물을 씻어낸 다음 결절을 두 번째 선박에 싣고 해안으로 다시 운반하여 처리합니다. 한편 남는 퇴적물은 대부분의 해양 생물보다 훨씬 낮은 수심인 약 1,500미터의 바다로 다시 방출됩니다. 이 프로젝트에 관심을 보이는 기업은 TMC뿐만이 아닙니다. 준설 대기업인 Deme의 자회사인 벨기에의 Global Sea Mineral Resources라는 회사도 관심을 갖고 있으며, TMC와 유사한 해저 로봇 및 라이저 시스템을 테스트했습니다. 베이징 파이오니어, 차이나 머천트, 차이나 민메탈 등 중국 기업 3곳도 뛰어들었지만 기술적으로 뒤처진다는 평가를 받고 있습니다.

육지에서 채굴할 때와 마찬가지로 바다에서 니켈을 채굴하면 주변 생태계가 손상됩니다. CCZ는 깊고 어둡고 차갑지만 생명이 없는 곳은 아닙니다. TMC의 로봇은 채취하는 결절에 서식하는 생물뿐만 아니라 로봇이 지나가는 많은 생물체를 파괴할 것입니다. 또한 퇴적물 기둥을 걷어 올리며, 그 중 일부는 인근 생물에게 떨어져 죽게 됩니다(연구에 따르면 기둥은 해저에서 2m 이상 올라가지 않는 경향이 있다고 합니다).

런던 자연사 박물관의 해양 생물학자 애드리안 글로버는 생명체가 바다에서 먼저 진화하고 나중에 육지로 이동했기 때문에 지구상의 유전적 다양성의 대부분은 여전히 수중에서 발견된다고 지적합니다. 심해저는 어둡고 영양분이 부족하지만, 그럼에도 불구하고 수천 종의 독특한 생물종이 서식하고 있습니다. 대부분은 미생물이지만 벌레, 해면 및 기타 무척추동물도 있습니다. 글로버 박사는 생명의 다양성이 "매우 높다"고 말합니다.

그러나 여러 측면에서 해저 채굴은 인도네시아에서 채굴하는 것보다 환경에 미치는 영향이 더 적습니다. 심해의 혹독한 환경으로 인해 서식 생물은 매우 다양할 수 있지만 그다지 풍부하지는 않습니다. 2016년에 <네이처>에 발표된 한 논문에 따르면, 1제곱미터의 CCZ에는 최대 무게가 몇 그램에 불과한 생물체 1~2마리가 서식하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 반면 인도네시아 열대우림 1제곱미터에는 식물 바이오매스만 약 30,000그램이 있으며 영장류, 조류, 파충류, 곤충까지 합치면 그보다 훨씬 더 많은 양이 있습니다.

하지만 단순히 각 생태계의 바이오매스 무게를 측정하는 것만으로는 충분하지 않습니다. 헥타르당 생산할 수 있는 니켈의 양도 중요합니다. TMC가 개발하고자 하는 2.5 헥타르의 해저에서 약 380만 톤의 니켈, 즉 헥타르당 약 1.5톤의 니켈이 생산될 것으로 예상됩니다.

육상 채굴을 하는 회사는 해저 채굴을 희망하는 회사보다 투명성이 떨어지기 때문에 육상 채굴에 대한 정확한 수치를 얻는 것은 까다롭습니다. 하지만 비영리 언론 매체인 퓰리처 센터의 조사 보고서에 따르면 인도네시아 니켈 산업의 중심지인 술라웨시 섬의 열대우림 1헥타르에서 약 675톤의 니켈이 생산될 것으로 예상됩니다. (광석의 품질이 낮음에도 불구하고 육상 매장지가 훨씬 더 많은 니켈을 생산하는 이유 중 하나는 광석이 해저에만 존재하는 반면, 니켈 결절은 지표면 아래까지 뻗어 있기 때문입니다).

이 모든 것이 매우 대략적인 비교를 가능하게 합니다. CCZ 니켈 1톤을 채굴할 때마다 약 13킬로그램의 바이오매스가 손실됩니다. 술라웨시에서 1톤을 채굴할 때마다 식물만 약 450kg이 파괴되며, 동물 바이오매스도 알려지지 않은 양이 파괴됩니다.

독을 고르세요

해저 채굴에 찬성하는 다른 환경적 주장도 있습니다. 해저 결절에는 육지의 퇴적물보다 훨씬 높은 농도의 금속이 함유되어 있어 이를 처리하는 데 더 적은 에너지가 필요합니다. 벨기에 루벤 지속 가능한 금속 및 재료 연구소의 피터 톰 존스 소장은 이 결절을 처리하면 육상 광석보다 온실가스 배출량이 약 40% 감소할 것으로 예상합니다.

어차피 가공을 위해 결절을 제거해야 하기 때문에 TMC와 같은 회사는 에너지 배출량이 적은 곳을 선택하도록 장려할 수 있습니다. 반면 인도네시아 니켈 광석은 채굴된 곳에서 가공하지 않으면 경제성이 떨어집니다. 이는 거의 항상 석탄 발전소나 디젤 발전기의 전기를 사용하는 것을 의미합니다. CRU의 분석가인 알렉스 라하른은 인도네시아의 니켈 생산이 니켈 1톤당 약 60톤의 이산화탄소를 배출한다고 말합니다. 런던에 본사를 둔 벤치마크 미네랄 인텔리전스(Benchmark Minerals Intelligence)가 실시한 TMC의 계획에 대한 감사에 따르면 해저에서 채취한 니켈 1톤당 약 6톤의 이산화탄소가 배출되는 것으로 나타났습니다.

어쨌든 해저에서 채취한 금속이 열대우림에서 채굴한 금속을 완전히 대체하기는 어려울 것입니다. 배터리 생산량이 너무 빠르게 증가하고 있기 때문에 니켈이 있는 곳이라면 어디에서든 채굴할 수 있을 것입니다. 하지만 해양 결절이 저렴하게 시장에 출시될 수 있다면, 사용 가능한 금속의 양이 많아져 인도네시아 삼림에 대한 압력을 완화할 수 있을 것입니다. 이러한 주장은 오랫동안 이론적인 수준에 머물지 않을 것입니다. TMC의 배런은 내년 말까지 해저에서 니켈과 다른 금속을 생산하는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다. ■

_정정(2023년 7월 6일): 이 기사의 이전 버전에서는 전 세계 니켈 생산량이 2040년까지 연간 4,800만 톤에 도달해야 하며, 2040년까지 총 3억 2,000만 톤이 될 것이라고 말했습니다. 정확한 수치는 630만 톤과 80만 톤입니다. 오류에 대해 사과드립니다.

Five things you need to know about deep-sea mining

Technology is being developed by mining companies to scrape the deepest part of the Pacific ocean for minerals that are key to fuelling the energy transition. The International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UN-backed regulator, is preparing to consider the world’s first commercial deep-sea mining application, even though regulations to govern the practice are still being drafted. But scientists worry that mining for metals in the deep sea could irreversibly damage a vast and largely untouched ecosystem.

Here is what you need to know:

What is deep-sea mining?

Deep-sea mining is the process of retrieving mineral deposits from the ocean below 200 metres—the deep seabed, which covers around two-thirds of the total seafloor. Submersible crafts equipped with giant suction pipes creep across the seabed in rows, stirring up metallic objects the size of potatoes. The polymetallic nodules are sorted, with unwanted sediment flushed back into the sea.

Mining the deep ocean floor has been discussed since the 1960s. But the transition to clean energy and ambitious climate targets have fuelled a growing interest in the mineral deposits found on the seabed, such as copper, nickel, aluminium, manganese, zinc, lithium and cobalt.

Demand for these metals to produce technologies like wind turbines, solar panels, batteries and smartphones is set to soar—the World Bank estimates that production of minerals will need to increase by nearly 500% by 2050 to meet the growing demand for clean-energy technologies.

Why are people talking about deep-sea mining now?

Two years ago the government of Nauru, an island nation in the south-western Pacific, notified the ISA of its intention to sponsor The Metals Company (TMC), a Canadian firm, to begin extraction from the deep seafloor. This triggered a legal clause forcing the ISA to adopt rules for deep-sea mining within 24 months. If the regulations have not been agreed on by next month, TMC can submit an application to go ahead with mining on an ad hoc basis.

A spokesman for TMC said that if the ISA decides to accept applications for mining, the company will only do so after it has completed an environmental and social impact assessment itself, ideally after the ISA has agreed on the regulations.

“The application review process as currently envisioned by the ISA is about a year long and we expect to begin first production by the end of 2024/beginning of 2025, assuming that our application is approved,” the spokesman said in an email statement.

The ISA has issued 31 contracts to explore more than 1.5m square kilometres of international seabed, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The ISA has been developing regulations for the extraction of minerals since 2014, with members struggling to agree on the framework that will govern this nascent industry.

What is the environmental impact of deep-sea mining?

The impacts are hard to predict, given that there are still huge gaps in scientific knowledge of the deep sea—over 75% of the seafloor remains unmapped, and less than 1% of the deep ocean has been explored. Environmental groups and scientists have raised concerns about mining going ahead before the impacts of extraction from the seabed are properly considered.

There are several areas of concern. First, the deep ocean absorbs and stores more than 90% of the excess heat and approximately 38% of the carbon dioxide generated by humanity. Breakdown of even a small fraction of carbon stored in marine sediments could exacerbate climate change, according to a report by conservation group Fauna and Flora International.

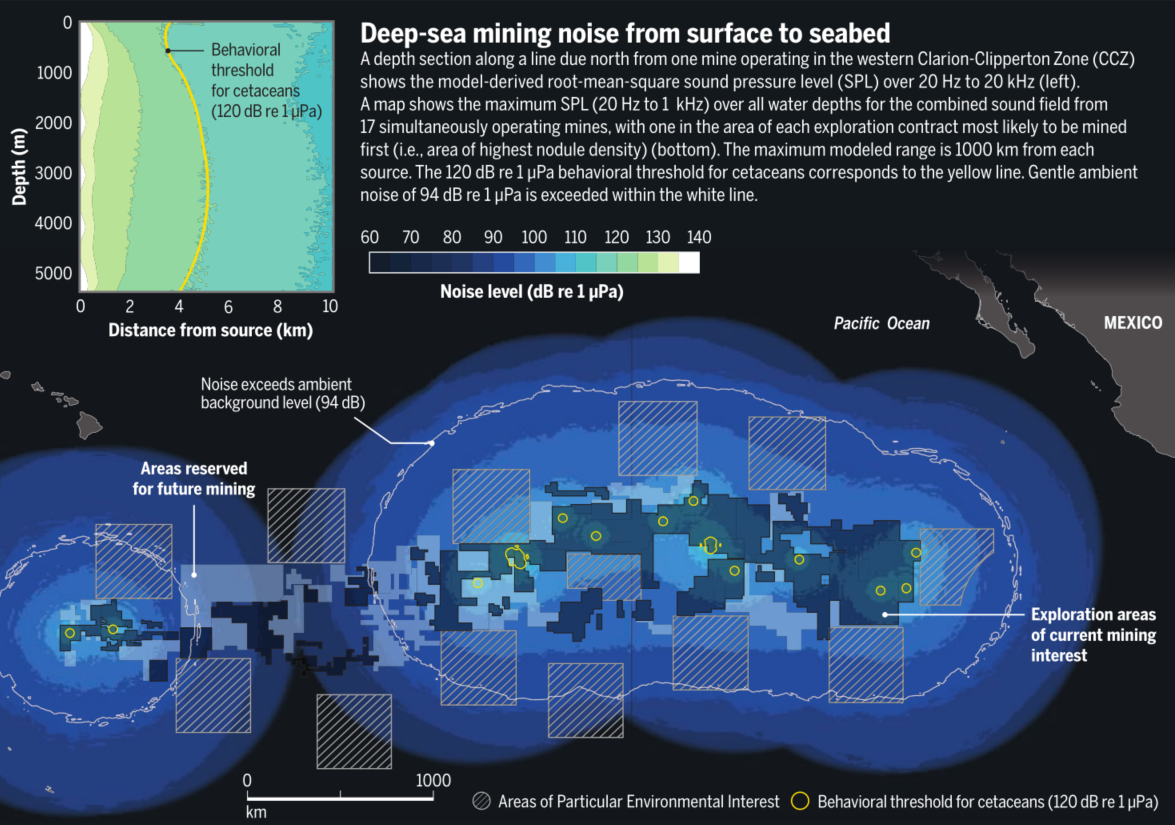

The noise from deep-sea mining could disrupt marine mammals, such as whales and dolphins, that use sound as a primary means of underwater communication and sensing. Other forms of pollution such as light from ships and machines, and potential leaks and spills of fuel and toxic products, could also damage delicate ecosystems and biodiversity.

As well as waste water discharged by mining ships at the ocean surface, another concern is the plumes of suspended particles that will be stirred up by the mining machinery. These plumes may disperse for hundreds of kilometres, take a long time to resettle on the seafloor, and affect ecosystems and commercially important or vulnerable species, scientists believe. For instance, such plumes could smother animals, harm filter-feeding species, and block animals’ visual communication.

There are also implications for the human rights of communities that could be affected by pollution or damaged fisheries, how the financial benefits of mining might be shared, and inadequate stakeholder engagement.

The area of most interest to miners is called the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), an area in the Pacific that spans roughly the width of the continental US. There are 17 contracts for mineral exploration covering 1.2m km2 in the CCZ, but baseline knowledge of the biodiversity in the region has been severely lacking until recently.

The first proper assessment of the biodiversity of the zone has now been carried out by scientists from the Natural History Museum. Commissioned by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the study found some 179 species that are unique to the area, and estimates that a further 6,000-8,000 more species unknown to science could live there.

What do mining companies say about the environmental impact?

TMC argues that the biggest threat to the oceans is climate change, and that the planet’s top priority should be to achieve net-zero emissions. To achieve this, trade-offs will be necessary, it says.

Although there are technically enough metal-bearing deposits on land to meet the needs of the transition to renewable energy, TMC and other mining companies argue that these resources cannot necessarily be extracted economically and without damage to the environment. Furthermore, land-based deposits of the metals found in the deep sea are located in some of the planet’s most biodiverse places, including Indonesia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa.

TMC believes that recycling spent EV batteries is part of the answer, but notes that the quantity will not be sufficient to keep up with demand in the near future. The International Energy Agency has estimated that recycling of minerals could reduce primary supply by around 10% by 2040. It sees a future where metals mined from the seabed will likely coexist with recycled metals for a few decades, but could be phased out as sufficient stocks of recycled metals become available.

What do governments and businesses think?

Several governments, including those of Germany, Spain, New Zealand, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Chile, Norway and the UK, support a moratorium on deep-sea mining until environmental regulations are in place. French president Emmanuel Macron has called for a complete ban.

Global brands and major users of battery technology including Samsung, Google, Volvo, Philips and BMW have also backed a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

심해 채굴에 대해 알아야 할 5가지 사항

광산업체들은 태평양의 가장 깊은 곳에서 에너지 전환의 원동력이 되는 광물을 채굴하기 위한 기술을 개발하고 있습니다. 유엔의 지원을 받는 규제 기관인 국제해저기구(ISA)는 심해 채굴에 관한 규정을 아직 마련 중이지만 세계 최초의 상업적 심해 채굴 신청을 고려할 준비를 하고 있습니다. 하지만 과학자들은 심해에서 금속을 채굴하는 것이 광활하고 거의 손길이 닿지 않은 생태계를 돌이킬 수 없을 정도로 훼손할 수 있다고 우려하고 있습니다.

심해 채굴에 대해 알아두어야 할 사항을 소개합니다:

심해 채굴이란 무엇인가요?

심해 채굴은 전체 해저의 약 3분의 2를 차지하는 심해저 200미터 아래의 바다에서 광물 매장량을 채굴하는 과정입니다. 거대한 흡입관을 장착한 잠수정들이 줄을 지어 해저를 가로지르며 감자만한 크기의 금속 물체를 끌어올립니다. 다금속 결절은 분류되고 불필요한 퇴적물은 다시 바다로 흘러들어갑니다.

심해저 채굴은 1960년대부터 논의되어 왔습니다. 그러나 청정에너지로의 전환과 야심찬 기후 목표에 따라 구리, 니켈, 알루미늄, 망간, 아연, 리튬, 코발트 등 해저에서 발견되는 광물 매장량에 대한 관심이 높아지고 있습니다.

풍력 터빈, 태양열 패널, 배터리, 스마트폰과 같은 기술을 생산하기 위해 이러한 금속에 대한 수요가 급증할 것으로 예상되며, 세계은행은 청정 에너지 기술에 대한 수요 증가를 충족하기 위해 2050년까지 광물 생산량을 500% 가까이 늘려야 할 것으로 예상하고 있습니다.

지금 사람들이 심해 채굴에 대해 이야기하는 이유는 무엇일까요?

2년 전 남서태평양의 섬나라 나우루 정부는 캐나다 회사인 더 메탈스 컴퍼니(TMC)가 심해저에서 채굴을 시작할 수 있도록 후원하겠다는 의사를 ISA에 통보했습니다. 이로 인해 ISA는 24개월 이내에 심해저 채굴에 대한 규정을 채택해야 하는 법적 조항이 발생했습니다. 다음 달까지 규정이 합의되지 않으면 TMC는 임시로 채굴을 진행하기 위해 신청서를 제출할 수 있습니다.

TMC의 대변인은 ISA가 채굴 신청을 받아들이기로 결정하면 회사는 자체적으로 환경 및 사회적 영향 평가를 완료 한 후에야, 이상적으로는 ISA가 규정에 동의 한 후에만 그렇게 할 것이라고 말했습니다.

대변인은 이메일 성명에서 "현재 ISA가 구상하고 있는 신청서 검토 절차는 약 1년 정도 소요되며, 신청서가 승인된다고 가정할 때 2024년 말 또는 2025년 초에 첫 생산을 시작할 것으로 예상합니다."라고 말했습니다.

국제자연보전연맹(IUCN)에 따르면 ISA는 1.5m 제곱킬로미터 이상의 국제 해저를 탐사하기 위해 31건의 계약을 체결했습니다. ISA는 2014년부터 광물 추출에 대한 규정을 개발해 왔으며, 회원사들은 이 초기 산업을 규율할 프레임워크에 합의하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있습니다.

심해 채굴이 환경에 미치는 영향은 무엇인가요?

심해에 대한 과학적 지식에는 여전히 큰 격차가 존재하며, 해저의 75% 이상이 지도화되지 않았고 심해의 1% 미만이 탐사되었다는 점을 고려할 때 심해 채굴이 미치는 영향은 예측하기 어렵습니다. 환경 단체와 과학자들은 해저 채굴이 심해에 미치는 영향이 제대로 고려되기 전에 채굴이 진행되는 것에 대해 우려를 제기하고 있습니다.

몇 가지 우려되는 부분이 있습니다. 첫째, 심해는 인류가 생성하는 과도한 열의 90% 이상과 이산화탄소의 약 38%를 흡수하고 저장합니다. 환경 보호 단체인 국제 동식물 보호협회(Fauna and Flora International)의 보고서에 따르면 해양 퇴적물에 저장된 탄소가 극히 일부만 분해되어도 기후 변화를 악화시킬 수 있다고 합니다.

심해 채굴로 인한 소음은 소리를 주요 수중 통신 및 감지 수단으로 사용하는 고래나 돌고래와 같은 해양 포유류의 청각에 장애를 일으킬 수 있습니다. 선박과 기계에서 나오는 빛, 연료 및 독성 제품의 잠재적인 누출 및 유출과 같은 다른 형태의 오염도 섬세한 생태계와 생물 다양성을 손상시킬 수 있습니다.

채굴 선박이 해수면에 배출하는 폐수뿐만 아니라 채굴 기계가 휘젓는 부유 입자 연무도 우려되는 부분입니다. 과학자들은 이러한 부유 입자 연기가 수백 킬로미터까지 흩어져 해저에 정착하는 데 오랜 시간이 걸리며 생태계와 상업적으로 중요하거나 취약한 종에 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 생각합니다. 예를 들어, 이러한 연기는 동물을 질식시키고, 여과식 먹이 종에 해를 끼치며, 동물의 시각적 의사소통을 차단할 수 있습니다.

또한 오염이나 어업 피해로 인해 영향을 받을 수 있는 지역사회의 인권, 채굴로 인한 재정적 이익의 공유 방식, 부적절한 이해관계자 참여에도 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.

광부들이 가장 관심을 갖는 지역은 미국 대륙의 너비에 해당하는 태평양 지역인 클라리온 클리퍼톤 광구(CCZ)입니다. CCZ에는 1.2㎢에 달하는 17건의 광물 탐사 계약이 체결되어 있지만, 최근까지 이 지역의 생물 다양성에 대한 기초 지식은 매우 부족했습니다.

이제 자연사 박물관의 과학자들이 이 지역의 생물다양성에 대한 최초의 적절한 평가를 수행했습니다. 퓨 자선 트러스트의 의뢰로 진행된 이 연구에서 이 지역에만 서식하는 179종의 생물이 발견되었으며, 과학적으로 알려지지 않은 6,000~8,000종의 생물이 더 서식할 것으로 추정하고 있습니다.

채굴 회사들은 환경에 미치는 영향에 대해 어떻게 말하나요?

TMC는 해양에 대한 가장 큰 위협은 기후 변화이며, 지구의 최우선 과제는 순배출량 제로를 달성하는 것이라고 주장합니다. 이를 달성하기 위해서는 절충안이 필요하다고 말합니다.

기술적으로 육상에는 재생 에너지로의 전환에 필요한 금속을 함유한 매장량이 충분하지만, TMC와 다른 광산업체들은 이러한 자원을 반드시 경제적으로, 그리고 환경에 피해를 주지 않고 추출할 수 있는 것은 아니라고 주장합니다. 게다가 심해에서 발견되는 금속의 육상 매장지는 인도네시아, 콩고민주공화국, 남아프리카공화국 등 지구상에서 가장 생물 다양성이 풍부한 곳에 위치해 있습니다.

TMC는 다 쓴 전기차 배터리를 재활용하는 것이 해답의 일부라고 생각하지만, 가까운 장래에 수요를 따라잡기에는 그 양이 충분하지 않을 것이라고 지적합니다. 국제에너지기구는 광물을 재활용하면 2040년까지 1차 공급량을 약 10% 줄일 수 있을 것으로 예상했습니다. 이 기관은 해저에서 채굴된 금속이 수십 년 동안 재활용 금속과 공존할 가능성이 높지만, 재활용 금속의 재고가 충분해지면 단계적으로 사라질 수 있다고 전망합니다.

정부와 기업은 어떻게 생각하나요?

독일, 스페인, 뉴질랜드, 에콰도르, 코스타리카, 칠레, 노르웨이, 영국을 포함한 여러 정부는 환경 규제가 마련될 때까지 심해 채굴을 유예하는 것을 지지하고 있습니다. 에마뉘엘 마크롱 프랑스 대통령은 전면 금지를 촉구했습니다.

삼성, 구글, 볼보, 필립스, BMW 등 글로벌 브랜드와 배터리 기술의 주요 사용자들도 심해 채굴 유예를 지지하고 있습니다.

Five things you need to know about deep-sea mining | Economist Impact

impact.economist.com

'주제별 자료 > 해안지형' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 해구 (Trench) (0) | 2022.01.29 |

|---|---|

| 몽셀미셀 (Mont Saint-Michel ) 간석지 (0) | 2021.09.29 |

| 모래질 간석지 사진 (0) | 2021.08.23 |

| 칭다오의 녹조(algae) - 황해를 목조르다 (0) | 2021.08.18 |

| '해안 침식 지형 vs 해안 퇴적 지형' 한 눈에 보이는 귀한 사진 (0) | 2021.06.09 |