The blurb for Rebecca Smith’s Rural: The Lives of the Working Class Countryside sells it as a call to arms for the countryside’s abused, exploited and forgotten working classes, and its most memorable passages resound with all the get-off-our-land fury of a gamekeeper’s shotgun.

“An Airbnb or a second home might bring in some money for the local shop, but it won’t bring more children to the school,” she writes, revisiting the town near where she grew up in the Lake District. “They won’t be on the fundraising committees for the pantomime or the summer dances, they won’t be part of the church congregation or able to organise the local ceilidhs… by buying a house to experience that for the few weeks, or even a few months of the year, they have gradually suffocated the life forever. Throughout these villages, UK-wide, country shows are being cancelled, pubs are closing down, hotels can’t get the staff and schools are shutting. We have reached the tipping point. Some areas might even have passed it.”

Prompted by her memories and questions, she travels to various rural communities with historical links to industry, each one given a chapter with a title such as “Coal”, “Water” or “Food”. The best are those in which she uncovers forgotten working-class histories and communities: the villages built for forestry workers as forests were planted after the first world war, for example, or the camps for the navvies who built the great dams and reservoirs to supply the cities with drinking water. Less compelling are the chapters such as “Mining” or “Textiles”, which add little to already familiar histories.

In her prologue Smith says she isn’t trying to provide an exhaustive account of the rural working class, but at times her selection does feel random and uneven. Her definition of “working class” is very much her own, based not on economics but on being connected to the landscape through work. This leads her to some odd choices of subject, notably tenant farmers rather than any farm labourers, who surely shaped more of the countryside than any other group of workers. It’s true that social class can work differently in rural areas – Marx himself decided that both the peasantry and the farmers were incapable of acting as classes, and felt they should just move into cities to join the struggle. But it is hard to grasp how certain topics – raves in a slate mine, for example – exemplify a distinct, contemporary rural working-class culture. It would have been interesting to hear her views on how and why they do.

The book is better read not as as a single, tidy argument but as a series of interconnected essays linked by Smith’s journey around the country. She was pregnant for much of the journey, and she details how that, and having to manage a family, affected her research. Some readers will find this intrudes on the main narrative, but she is making the point that if you are not well off, and your circumstances are challenging, then a sense of a family connection to a place can feel like the most important thing you have, and have to give. How we manage people’s competing claims to ownership of places is one of the great questions for the world in the 21st century. As Rural shows, the British countryside is a good example of how not to do it.

For anyone with experience of country ghost towns that come alive only when the second-homers’ 4x4s roll in on Friday night, this feeling will be infuriatingly familiar. The ongoing displacement of local communities makes Rural feel timely, but it has a wider range of targets than the familiar villains of the interloping urban Farrow & Ball set. Its strength is Smith’s sharp eye for new examples of urban money breaking up the relationships between local people and their landscapes. Corporations who offset their pollution by planting thousands of trees in inappropriate locations where the saplings will die off anyway; absentee landlords who shorten tenancy agreements so farmers can’t plan long-term improvements of the land; the gentry sacking estate workers and hawking their heritage to the leisure industry. For the roughly 20% of Britons who live in rural areas, such trends debilitate in the same way that gentrification does in cities. Smith conveys the emotional and psychological impacts of that without going full Royston Vasey on us, which is no small achievement.

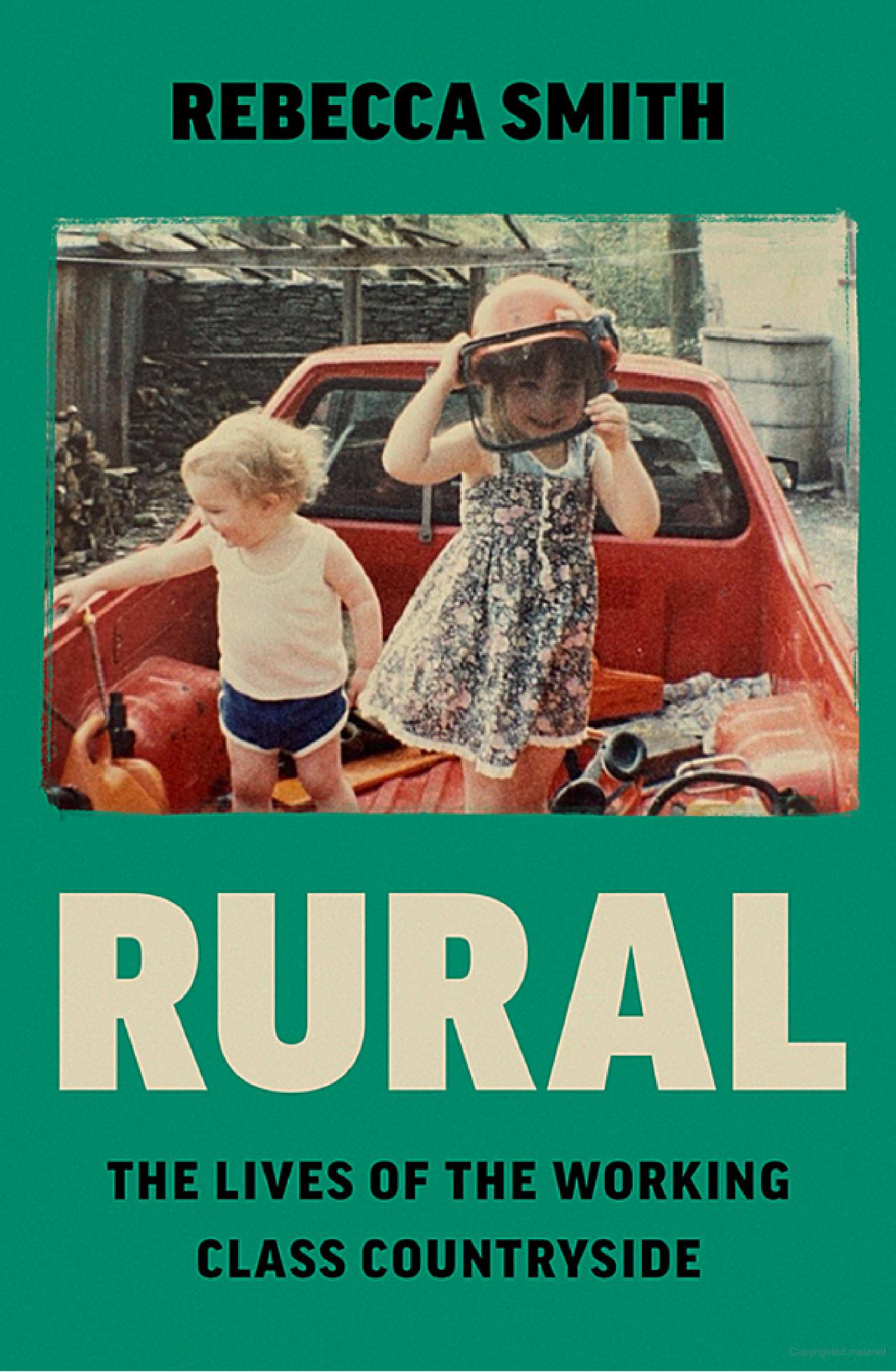

The book starts like a memoir. Smith lives with her partner and young children in a modern house on a 600-home housing development in Falkirk. Oppressed by the area’s lack of natural greenery, she spends a lot of time with her children in a nearby country park. Here she finds the remains of an old stately home, which reminds her of her poor but happy childhood spent in tied houses on country estates where her father worked as a forester.

“Our homes were old, damp and cold, and we were four miles from any kind of shop,” she recalls of those days. “But it was idyllic.” Her personal idyll was one of woodland wanderings, pheasant shoots and other visceral, muddy pleasures, but it’s distinguished by the social niceties of landed estate living; as a teenager, she had to learn to change her accent when answering the phone depending on whether it was a landowner or a friend calling. You can see where her interest in class comes from.

레베카 스미스의 농촌: 시골의 노동 계급의 삶은 시골의 학대받고 착취당하고 잊혀진 노동 계급을 위한 호소문으로 판매되고 있으며, 가장 기억에 남는 구절은 게임 키퍼의 산탄총에 대한 모든 분노로 울려 퍼집니다.

"에어비앤비나 세컨드 하우스는 지역 상점에 약간의 수입을 가져다줄 수는 있지만 학교에 더 많은 아이들을 데려오지는 못합니다."라고 그녀는 레이크 디스트릭트에서 자란 곳 근처의 마을을 다시 방문하며 글을 씁니다. "그들은 무언극이나 여름 무용을 위한 기금 모금 위원회에 참여할 수도 없고, 교회 회중의 일원이 될 수도 없으며, 지역 카일리드를 조직할 수도 없습니다... 집을 사서 몇 주 또는 일 년 중 몇 달 동안만 살면서 서서히 삶이 질식하는 것을 경험하게 됩니다. 영국 전역에서 컨트리 공연이 취소되고, 펍이 문을 닫고, 호텔이 직원을 구하지 못하고, 학교가 문을 닫는 등 마을 전체가 어려움을 겪고 있습니다. 우리는 티핑 포인트에 도달했습니다. 일부 지역은 이미 그 시점을 지났을 수도 있습니다."

그녀의 기억과 질문에서 영감을 받아 그녀는 산업과 역사적 연관이 있는 여러 시골 마을을 여행하며 각 마을에 '석탄', '물' 또는 '음식'과 같은 제목을 붙였습니다. 예를 들어, 제1차 세계대전 이후 숲을 조성하면서 임업 노동자들을 위해 지어진 마을이나 도시에 식수를 공급하기 위해 거대한 댐과 저수지를 건설한 해군 캠프 등 잊혀진 노동 계급의 역사와 공동체를 발견하는 챕터가 가장 흥미롭습니다. '광업'이나 '섬유'와 같이 이미 익숙한 역사에 새로운 내용을 추가하는 장은 그다지 매력적이지 않습니다.

스미스는 프롤로그에서 농촌 노동 계급에 대한 철저한 설명을 제공하려는 것이 아니라고 말하지만, 때때로 그녀의 선택은 무작위적이고 고르지 않은 느낌을 줍니다. "노동 계급"에 대한 그녀의 정의는 경제학이 아니라 일을 통해 풍경과 연결되는 것을 기반으로 한 매우 자신 만의 것입니다. 그래서 그녀는 다른 어떤 노동자 집단보다 시골을 더 많이 형성한 농장 노동자가 아닌 소작농을 주제로 삼는 이상한 선택을 하기도 합니다. 마르크스 자신도 농민과 소작농 모두 계급으로서 활동할 수 없다고 판단하고 도시로 이주해 투쟁에 참여해야 한다고 생각했기 때문에 농촌에서 사회 계급이 다르게 작동할 수 있다는 것은 사실입니다. 그러나 슬레이트 광산에서의 열광과 같은 특정 주제가 어떻게 뚜렷한 현대 농촌 노동 계급 문화를 보여주는지 이해하기는 어렵습니다. 그 이유와 방법에 대한 그녀의 견해를 듣는 것은 흥미로웠을 것입니다.

이 책은 하나의 깔끔한 주장이 아니라 스미스의 전국 여행으로 연결된 일련의 상호 연결된 에세이로 읽는 것이 더 좋습니다. 그녀는 여정의 대부분을 임신 중이었으며, 임신과 가족을 돌봐야 하는 상황이 연구에 어떤 영향을 미쳤는지 자세히 설명합니다. 일부 독자는 이것이 주요 내러티브에 방해가 된다고 생각할 수 있지만, 스미스는 형편이 넉넉하지 않고 환경이 어려울수록 한 장소에 대한 가족적 유대감이 가장 중요하고, 베풀어야 할 것 같은 느낌을 줄 수 있다는 점을 강조하고 있습니다. 장소에 대한 소유권에 대한 사람들의 경쟁적인 주장을 어떻게 관리할 것인가는 21세기 전 세계가 직면한 큰 문제 중 하나입니다. Rural이 보여주는 것처럼 영국의 시골은 그렇게 하지 않는 좋은 예입니다.

금요일 밤에 세컨드 홈족의 4x4 차량이 들어올 때만 활기를 띠는 시골 유령 마을을 경험한 사람이라면 이런 느낌이 매우 친숙하게 느껴질 것입니다. 지역 사회의 지속적인 이주로 인해 Rural은 시의적절하게 느껴지지만, 도시를 배경으로 한 Farrow & Ball 세트의 익숙한 악당들보다 대상의 범위가 더 넓습니다. 이 작품의 강점은 도시 돈이 지역 주민과 풍경 사이의 관계를 깨뜨리는 새로운 사례에 대한 스미스의 예리한 시선입니다. 어차피 묘목이 고사할 부적절한 장소에 수천 그루의 나무를 심어 오염을 상쇄하는 기업, 농부들이 장기적인 토지 개선 계획을 세울 수 없도록 임대 계약을 단축하는 부재지주, 부동산 노동자들을 약탈하고 그들의 유산을 레저 산업에 팔아넘기는 젠트리 등이 그 예입니다. 농촌 지역에 거주하는 약 20%의 영국인에게 이러한 경향은 도시에서 젠트리피케이션이 일어나는 것과 같은 방식으로 그들의 삶을 약화시킵니다. 스미스는 로이스턴 베이시처럼 감정적이고 심리적인 영향을 우리에게 고스란히 전달하고 있으며, 이는 결코 작은 성과가 아닙니다.

이 책은 회고록처럼 시작됩니다. 스미스는 포커크에 있는 600가구 규모의 주택 개발에 있는 현대식 주택에서 파트너, 어린 자녀와 함께 살고 있습니다. 이 지역에 자연 녹지가 부족한 것이 아쉬웠던 그녀는 인근의 시골 공원에서 아이들과 많은 시간을 보냅니다. 이곳에서 그녀는 아버지가 산림 관리인으로 일하던 시골 영지에서 가난했지만 행복했던 어린 시절을 떠올리게 하는 낡고 웅장한 집터를 발견했습니다.

"우리 집은 낡고 습하고 추웠으며 상점이 있는 곳으로부터 4마일이나 떨어져 있었습니다."라고 그녀는 당시를 회상합니다. "하지만 목가적이었죠." 개인적으로는 숲 속을 돌아다니고 꿩을 잡는 등 본능적이고 진흙탕 같은 즐거움을 누렸지만, 10대 시절에는 전화를 받을 때 지주인지 친구인지에 따라 억양을 바꾸는 법을 배워야 할 정도로 지주 집안 생활의 사회적 예의가 중요했습니다. 수업에 대한 그녀의 관심이 어디에서 비롯되었는지 알 수 있습니다.

Rural by Rebecca Smith review – a personal study of working-class life in the countryside

Her timely defence of blue-collar rural communities works best when the Cumbrian author explores how urban money severs the links between locals and their landscape

www.theguardian.com

'문서자료 > 책' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Vertical Coordination in Agriculture (1963) (0) | 2023.07.24 |

|---|---|

| 책 소개 The Three Ages of Water by Peter Gleick (2023) (0) | 2023.07.02 |

| 책소개 'Black Geographies' (0) | 2021.09.19 |

| Geographies of Race and Food - Fields, Bodies, Markets 목차 (0) | 2021.06.23 |

| Food & Place - A Critical Exploration 목차 (0) | 2021.06.23 |