2008년 이후 2022년 4월 기준 지난 12개월간 아일랜드 인구가 최고로 증가했음

(자연증가 + 사회적 증가 = 88,800명 증가)

(+) 120,700명 해외 유입

1) 28,900명 = 고국으로 돌아온 아일랜드인

2) 24,300명 = 기타 EU 국민

3) 4,500명 = 영국 국민

4) 63,000명 = 28,000명의 우크라이나 외 기타 국민

(-) 59,000명 해외 유출 (전년도 54,000명에 비해 증가추세)

(+) 27,700명 = 자연증가 (60,700명 출생 - 33,000명 사망)

https://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/ireland-sees-largest-jump-in-population-in-14-years-1354376.html

Ireland sees largest jump in population in 14 years | BreakingNews.ie

A combination of a natural increase and migration led to population growth of 88,800 in the year to April.

www.breakingnews.ie

“We’ve been saving for the last two years,” says Críomhthann McCarthy, 32, a youth worker from County Tipperary in Ireland. He and his partner of four years, Aileen Sheehan, 35, each live with their parents while they try to save for a house.

“We’re racing against inflation in house prices while our savings are deflating against house price inflation,” he says. “If you look too closely, it looks a little hopeless.”

Ireland has traditionally been a nation of homeowners and property has made one in eight households a millionaire on paper. But getting on to the property ladder is out of reach for many now — and for an increasing number of people, simply securing a place to live is getting harder.

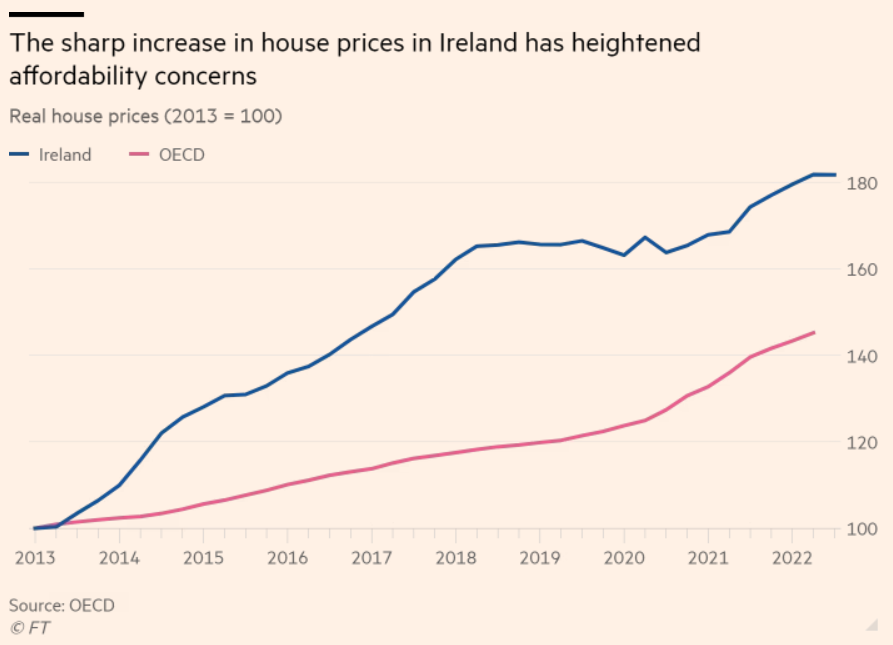

Even by the standards of property markets in similar developed nations, Ireland has seen a surge in house prices over the past five years — just over a decade after a previous boom-bust cycle brought on an economic crisis.

But unlike other hot global property markets that are facing a rapid cool-down as interest rates rise and recession looms, Ireland’s boom shows no signs of slowing: it is still facing a housing shortage that is driving up prices, whether it is to buy or to rent.

House prices rose nearly 10 per cent nationwide in the year to October, down a percentage point from the year to September, according to the Central Statistics Office, with the median price of a property in the year €300,000. In parts of the west of Ireland, property prices rocketed more than 16 per cent. Property prices nationally have increased 130 per cent since early 2013, the CSO says.

At the same time, Ireland has seen “an extraordinary collapse in the stock available to rent” in the past 18 months, according to Ronan Lyons, a Trinity College Dublin professor and housing expert, in a report for property site Daft.ie.

He found just 495 homes available to rent in Dublin on July 1 and only 35,000 nationwide, virtually half the level available in 2016.

However, nationwide rents rose by an average of 14.1 per cent in the third quarter this year compared with the same period in 2021, according to Daft.ie — the highest increase since it began tracking rents in 2005.

The government says the €4bn a year housebuilding programme it launched in 2021, called Housing for All, is working and is on course to exceed its construction target this year.

But population figures suggest Ireland is going to need to double its ambition. Ireland’s population has risen to 5.1mn, the country’s highest level since 1841 and an increase of 7.6 per cent compared with the last census in 2016. Ireland has also taken in more than 62,000 Ukrainian refugees.

“Preliminary Census 2022 figures suggest that underlying housing need in Ireland over the coming three decades is likely to be in the range of 42,000 to 62,000 homes [per year], not far off twice the underlying level of 28,000 new homes per year that underpins Housing for All,” wrote Lyons.

Ireland risks locking a generation out of home ownership and into unaffordable rentals, while condemning record numbers to homelessness. According to official figures, Ireland had an unprecedented 11,397 people in emergency shelters in October, but experts say rough-sleepers, couch-surfers and other “hidden homeless” are not included, meaning the true problem is even greater.

“We had accelerated house building from 1997-2009 and a massive drop back since,” says Rebecca Moynihan, a Labour senator and the party’s spokesperson on housing. “We don’t have additional stock and we have an exploding young population . . . This will probably get worse before it gets better.”

For a nation that has transformed itself in recent decades from a poor, rural, church-controlled backwater to a rich, socially progressive outward-looking state, the housing crisis is a chastening reality check that blights its open-for-business image.

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar admits multinational investors regularly raised the housing problem with him when he was trade minister, a role he held from 2020 to December 17, when he took over as premier for the second half of the coalition government’s term as part of a long-scheduled reshuffle.

One senior figure at a major tech company in Dublin — one of the industries that is powering Ireland’s economy and on which it relies for a corporate tax bonanza — admitted housing was a serious problem for staff. The company, they say, tried to ensure workers could “have their best experience” in places like Greystones or Balbriggan — quiet commuter towns on the coast, 30km south, and 45km north, of Dublin city centre respectively.

Housing is an especially sore subject in Ireland because lending for property fuelled the country’s Celtic Tiger boom from the mid-1990s. That ended up crashing the entire economy more than a decade later and requiring a €67.5bn IMF and EU bailout in 2010.

Now, a lack of housing is creating a new rift in society. In a country where people used to emigrate to escape poverty and seek work, as many as seven out of 10 young people are considering moving abroad because they cannot afford somewhere to live — an embarrassing failure for one of the EU’s better-off nations.

Stevie Wilson, a 23-year-old artist, is contemplating moving to Spain because of the problems her generation face in finding affordable housing. “I don’t think that unless I move country I can ever hope to own [a home],” she says.

Seeds of a crisis

Ireland used to be far better at building homes. Up until the property crash of 2008, Ireland had the highest rate of house completions among 19 EU countries surveyed, nearly three times most other states.

Indeed, in the early decades of the Irish Free State, formed in 1922, the government was the country’s largest homebuilder, delivering 112,144 social homes between the early 1930s and mid-1950s. That was more than half of all new housing built.

It helped clear people out of unsafe inner-city slums, according to Michelle Norris, a housing expert and professor of social policy at University College Dublin.

But the seeds of today’s crisis were sown with the country’s decision to sell off social housing to tenants without replacing it at the same rate, say economists and experts who have studied the problem.

“We always had quite a strong tenant purchase policy. But in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, we were building enough council housing to replace it,” says Rory Hearne, a lecturer in social policy at Maynooth University and author of Gaffs, a new book on Ireland’s housing crisis. “The problem was when we stopped replacing it.”

As Dara Turnbull, research co-ordinator at Housing Europe, a federation of public, co-operative and social housing providers across the continent, put it: “About two-thirds of all the social housing that we built in the history of the state is now in private hands. That’s it. That’s the whole story.”

Before the 1970s, Ireland did not have much in the way of private property development as the state was in the driving seat. But private financing then became “very effective” at creating supply, boosted by bank lending and fairly lax planning regulations, Norris said.

Housing output rose by 177 per cent between the boom years of 1996 and 2006, according to Norris, when house prices also rose nearly 300 per cent. The Celtic Tiger was driven by reckless lending and a property splurge; by its twilight, Ireland was building some 90,000 houses a year.

But in the austerity period that followed, social house building collapsed by 90 per cent to fewer than 760 units in 2013 and 2014, versus 8,763 in 2007.

Instead of the government leading the provision of low-cost housing for the worst off, private housing projects from 2000 were required to include 20 per cent of social housing within their developments.

As social housing stock fell — owing to developers not building as much as the government coupled with the sale of council homes — people had to be accommodated within the costlier private rental sector.

“Now, a third of all people in the private rentals are people who should be in social housing and receive a social housing subsidy,” Hearne says. He reckons that meant €1bn a year was going to private landlords to subsidise social housing.

Light-touch regulation of the short-stay market is compounding the problem, Hearne says, noting that Airbnb had more than 15,000 properties listed in Ireland, more than 10 times the number of long-term rental properties available.

Photos shared on social media in recent months capture the public’s frustration: queues of would-be renters chasing overpriced properties snaking round an entire block in a Dublin street is a tangible reminder of how little there is available to renters.

As demand has surged, so have rents. Between 2010 and the second quarter of this year, average rents rose by 82 per cent in Ireland, bank lobby group the Banking and Payments Federation Ireland noted in a recent report, far outstripping an EU average of 18 per cent.

“The idea that social and affordable housing is radical is bananas,” says Sian Ní Mhuirí, 33, who earns an above average industrial wage in the children’s animation industry. “Housing has become a source of investment, speculation or retirement, not a basic human right.”

Political promises

The housing crisis has become the most urgent political issue in Ireland. Irish voters see housing as the government’s biggest failing, giving Varadkar a political impetus to boost progress before elections due by early 2025.

According to a Red C poll last month, 84 per cent of people considered the government was performing poorly on housing. Almost 60 per cent thought they were doing very badly.

Nationalist party Sinn Féin has become Ireland’s most popular political force by zeroing in on the housing problem. It promises to dramatically accelerate homebuilding, cap bank rates and abolish local property tax.

Sinn Féin also wants to use a leasehold model. Eoin Ó Broin, housing spokesman for Sinn Féin, argues that the government could contract construction of homes on public land — eliminating site servicing and development costs, resulting in cheaper houses, with the state keeping ownership of the land.

But the condition would be if owners of those homes wanted to sell them, the properties would be offered only to other people who qualified for the housing scheme, rather than being put up for sale on the private market. That would create “a sub-market of privately owned, privately traded, permanently affordable homes,” Ó Broin says.

Ireland also has nearly 170,000 vacant properties and Ó Broin told the Financial Times that a quarter of the 20,000 social and affordable homes needed could come from repurposing vacant and derelict properties.

Even voters turned off by Sinn Féin, a pro-Irish unity party that was once the political wing of the republican paramilitary IRA, acknowledge it has done its homework. “The success or failure of this government . . . of the next government will be on housing,” Ó Broin says.

Varadkar has made clear housing is top of his to-do list, telling national broadcaster RTÉ he “genuinely” believed progress had been made in the government’s first two-and-a-half-years, “but it isn’t enough”.

He said he would sit down with experts to see how to accelerate implementation of Housing for All and try new tactics to “dramatically increase supply” and exceed 2023’s targets.

Varadkar has also urged young people not to emigrate for housing, saying the grass often looked greener abroad. Nonetheless, he has described the country’s housing crunch as “an emergency”, “a crisis”, “a social disaster” and “a drag” on foreign direct investment.

His housing minister has a more optimistic view of progress. “Of course there are ongoing challenges to the delivery of housing,” Darragh O’Brien said in comments to the FT. “But the plan is taking hold.”

He cited official data showing the record numbers of homes completed in the first nine months of this year — higher than any year since 2011, when the national statistics office began collecting such data. “I expect the government’s target of 24,600 homes in 2022 to be exceeded, with some commentators forecasting up to 28,000 completions this year,” he added.

O’Brien said there was “no silver bullet”. But new approaches, such as state-backed “cost-rental” tenancies — rentals to people on middle incomes above the threshold for social housing that exclude building and maintenance costs and are at least 25 per cent cheaper with no profits for developers — “means prices are not driven by market movements, making it more affordable”.

But the government also has to reckon with inflation that is driving up the cost of construction and higher interest rates pushing up the cost of finance.

Dermot O’Leary, chief economist at stockbrokers Goodbody, says higher rates “are causing an issue for build-to-rent apartments which has really been the major driver of growth in supply in the last two years. That’s under threat now”.

Lorcan Sirr, a senior lecturer in housing, planning and development at Technological University Dublin, says Ireland has “engineered a situation whereby the provision of social housing and private housing is pretty much dependent on rising house prices”.

Housing starts were 17 per cent lower in October compared with September, and a drop of 31 per cent compared with a year earlier and 63 per cent from the most recent peak, in May 2021. That will delay completions just around the time, in the run-up to the next election, that Varadkar will be wanting to tout progress.

O’Leary says there was also a 41 per cent drop in planning permissions granted in the third quarter compared with June-September last year, driven by a 66 per cent plunge in approvals for apartments.

“[The government] will overachieve in terms of their output targets this year, so they can argue we’re going in the right direction. But I can see the difficulties coming down the tracks,” O’Leary said.

The cabinet last week proposed a shake-up of the planning system that it says will help speed up housing construction, but O’Leary says that was “not a panacea to the supply problems . . . particularly in the short term”.

For Sirr, a social contract based on home ownership — the model Varadkar calls Ireland’s “homeowning democracy” — is under threat. The country’s home ownership rate is at 1971 levels, according to official data.

“It’s a financial reality that if you want to get anywhere in Ireland or be safe and secure in your dotage, you need to own property,” Sirr says. “[The government] has a huge plan to turn us all into renters, it looks like.”

Whereas once people would have paid off a mortgage by the time they retired, more people will face the challenge of keeping up rent payments after they stop work.

McCarthy, the youth worker, still dreams of buying a home. But he plans to vote for Sinn Féin in the next election. “The government now are doing everything they can but they spent decades not doing everything they could,” he says.

Other young people may not stick around until 2025. “When I’m older, I do want to live in Ireland,” says student Maria Puzone. “But my parents don’t own their own house . . . Rents are so high, it’s unfair on us . . . This is affecting our whole future.”

https://www.ft.com/content/ad969594-cb0e-483d-a761-b50b161fd428

Irish property: the boom that shows no signs of slowing

While other markets cool off, Ireland is facing a housing shortage that is driving up the cost of renting and buying

www.ft.com

------------------------------------

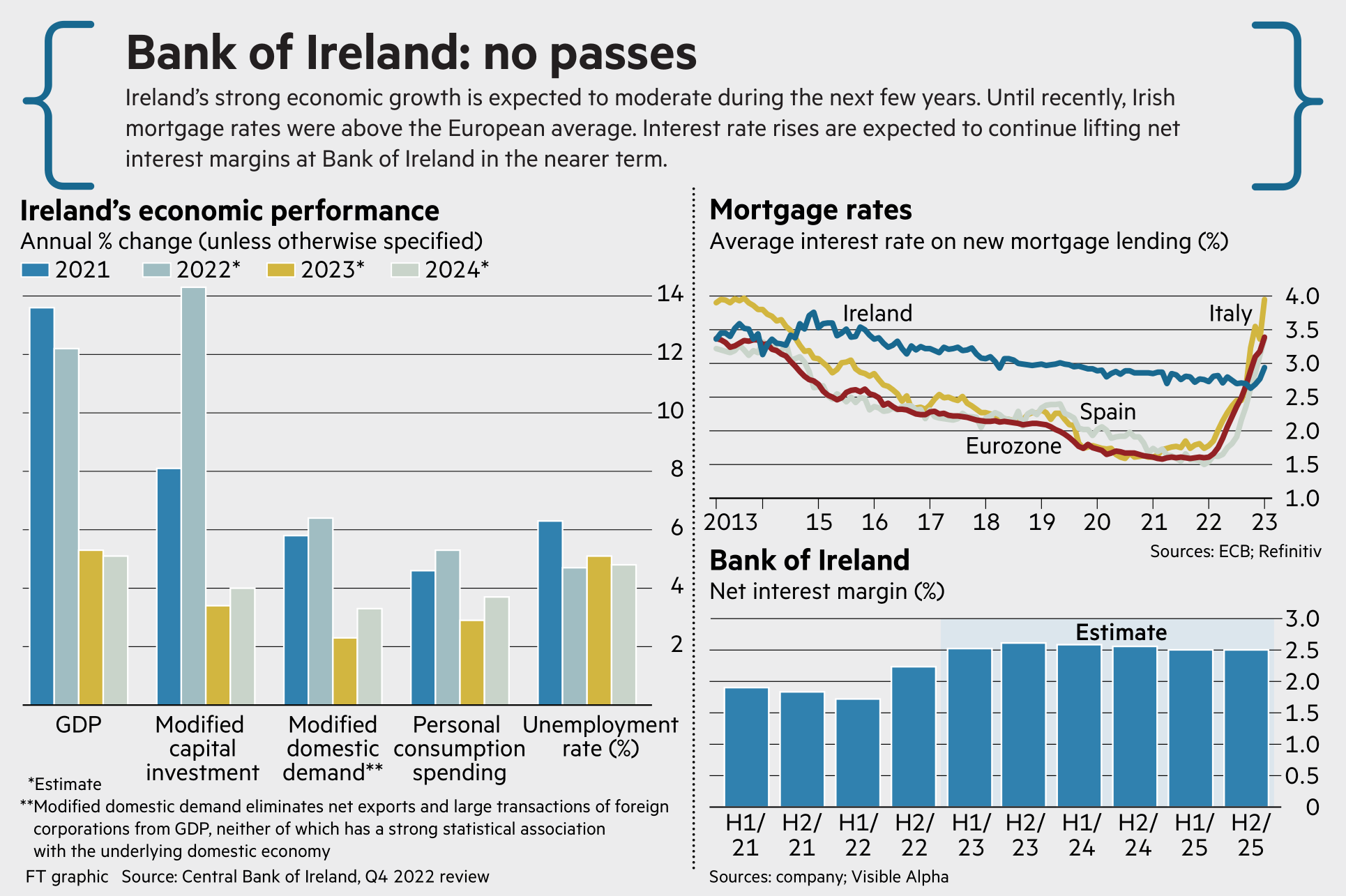

Belying its temperate climate, Ireland’s economy is prone to extremes. It had a terrible financial crisis and a bad pandemic. But it recovered strongly in 2022, a trend reflected in the fortunes of its banks. Higher interest rates, diminished competition and the activities of locally based multinationals have driven a strong run.

Irish banks outperformed European peers in 2022. Bank of Ireland, which reported results yesterday, has done best of all. Its shares rose 80 per cent while rival AIB registered a 70 per cent increase. Both have added a further 15 per cent since the start of 2023.

Bank of Ireland produced underlying profits before tax of €1.2bn last year. Stronger net interest income played a part, rising 12 per cent. The bank’s net interest margin in the second half was 2.2 per cent, some 47 basis points higher than in the first six months. Negative rates on €83bn of customer deposits still made a positive, if shrinking, contribution to NII during the second half.

Limited “pass through” of higher rates to savers is one reason strong performance may continue. Irish banks have not been disclosing what proportion they have been handing on. Analysts estimate the number at 5 per cent, or about a third of the eurozone average. Limited competition in Irish banking should keep a lid on that figure as income from lending follows rates higher.

The bank is targeting a return on tangible equity of 15 per cent from now until 2025. The common equity tier one ratio ended last year at 15.4 per cent, which included €350mn of distributions. A target ratio of 14 per cent highlights €660mn of spare capital, equivalent to 6 per cent of the current market worth. Dividends will push the yield higher still.

Shares in Bank of Ireland were at a discount to book value of a half a year ago. Unusually for a European bank, they are now at a premium of a 10th. The rally may have further to run but watch out for economic weakening in the current half year.

.

아일랜드의 빠른 克英 성장

.

우리나라와 아일랜드는 각각 일본과 영국의 식민지를 경험한 국가라는 점에서 공통점을 갖는다. 아일랜드는 수백 년간의 영국의 지배를 받았고 1845년~52년간에는 감자 흉작으로 대기근이 발생해 100만 명이 굶어 죽고 100만 명이 이민을 떠났던 나라다.

그럼에도 최근 아일랜드의 빠른 성장은 식민 지배를 한 국가를 뛰어넘어 경제 측면에서 이미 영국을 넘어서는, 즉 克英의 단계에 이르고 있다. 인구도 적고 국토도 좁은 나라의 특수한 사례라고 치부하기에는 그 성취가 너무도 대단하다. 아시아에 한국이 있다면 유럽에는 아일랜드가 있다.

아일랜드는 영국으로부터 오랜 기간 침략과 수탈, 지배를 당한 경험을 갖고 있다. 그러면서도 끈질기게 독립운동을 해 나가면서 영국의 지배에 맞서 싸웠다. 우여곡절 끝에 독립을 쟁취했지만 북아일랜드가 영국에 잔류하기로 결정하면서 아일랜드는 남북으로 쪼개졌다. 1949년에 공화국을 선포하면서 영국 연방에서 탈퇴하여 아일랜드공화국으로 공식 출범하였다.

2008년도에 아일랜드 경제의 특징들을 살펴볼 기회가 있었다. 그 당시 아일랜드가 주목의 대상이 되었던 이유는 구조개혁을 통해 외국인 직접투자를 유치하는데 성공하고 있었고 또 법인세의 과감한 인하, 경제 자유 및 개방의 확대, 노동시장의 안정 그리고 FDI 기업에 대한 R&D 지원 등 주목할 만한 정책들을 내놓고 있었기 때문이다. 정말 아일랜드는 과감한 구조조정과 개혁·개방을 바탕으로 급속한 경제발전을 이룬 대표적인 나라 가운데 하나이다. 더구나 우리 처럼 식민지 지배를 받은 경험을 갖고 있는 유럽에 위치한 나라 중 하나이다.

1980년대 중반 유럽에서 가장 빈국인 아일랜드에 경제 위기가 찾아와 국민 모두가 고통을 겪고 있었다. 경제 위기를 맞아 장차 나라의 운명을 바꾸는 두 개의 대타협이 이뤄졌다. 하나는 앙숙이었던 정치가들이 대화합을 이뤄낸 것이고, 다른 하나는 노사정이 대타협을 이뤄낸 것이다.

아일랜드 사회연대협약은 경제․사회 주체들 간의 합의를 통해 노․사 간의 임금 인상 가이드라인과 함께 거시적․미시적 경제정책을 위한 기본정책을 포함하고 있었다. 이 협약을 통해 이룩한 사회 및 노사 안정은 아일랜드의 지속적인 경제성장의 밑거름이 된 것으로 보인다. 아일랜드는 이러한 사회연대협약의 성공을 기반으로 1990년대 들어 적극적인 외국인 투자 유치 정책을 폈다. 안정적이고 예측 가능한 임금 상승률, 이에 따른 노사관계 안정은 외국 기업이 안심하고 투자할 수 있는 중요한 여건을 제공하였다.

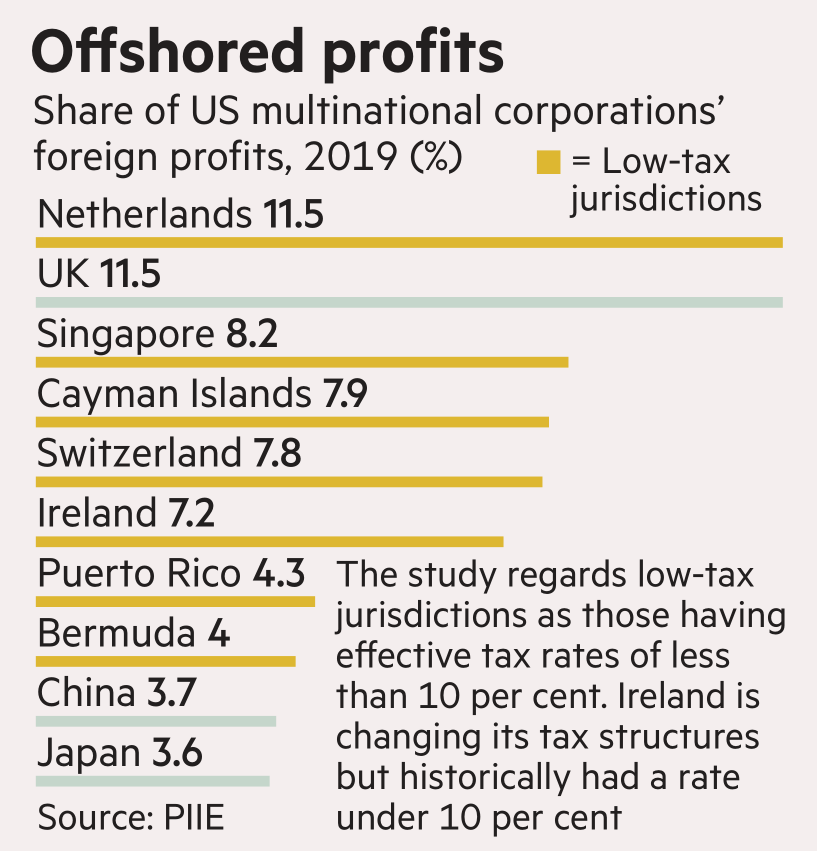

2003년 이후부터 적용되고 있는 12.5%의 유리한 법인세율 또한 아일랜드가 FDI 목적지가 되기에 매력적인 조건이 되었다. 이는 유럽 연합(EU)에서 두 번째로 낮은 세율이었다. 아일랜드에서 기업들은 주로 영어로 의사소통이 가능하며 고품질이며 유연한 인력, 다양한 언어를 구사하는 노동력을 쓸 수 있는 장점이 있었고, 노사관계는 협력적이고, 정치는 안정되어 있고, 정부 정책이나 규제 당국은 사업친화적이어서 아일랜드에 외국인 직접투자가 많이 들어왔다. 더구나 2021년 1월 1일 영국이 EU를 떠난 브렉시트 이후, 아일랜드는 EU 내 유일한 영어권 국가가 되면서 FDI의 최종 목적지로서 더욱 매력적인 국가가 되었다.

아일랜드 경제는 2021년에 13.5%의 GDP 성장률을 기록하였다. 이 성장 대부분은 수출 중심 산업(기술, 제약, 기타 대규모 다국적 기업)의 성장에 기인하고 있다. 아일랜드 정부는 외국인 직접 투자를 적극적으로 유치하고 있으며, 특히 미국 기업의 투자를 성공적으로 유치하고 있다. 아일랜드에는 화학, 생명 과학, 제약 및 의료기기; 컴퓨터 하드웨어 및 소프트웨어; 인터넷 및 디지털 미디어; 전자 및 금융 서비스 등 다양한 분야에서 운영하는 950개 이상의 미국 자회사가 들어와 기업활동을 하고 있다.

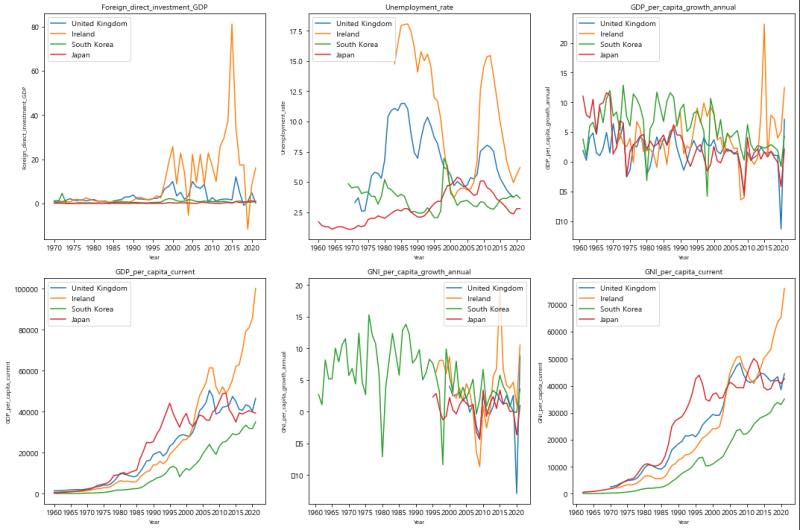

아래의 그래프는 The World Bank가 생산해 내는 WDI 데이터 베이스에서 다운로드한 자료들을 파이선 프로그램을 통해 시각화 한 것이다. 챗GPT와 대화하면서 만들어낸 기초자료 생성과 관련된 파이선 프로그래밍 과정에 대해서는 이 글과 동시에 포스팅하는 <파이선 초보자 맨땅 헤딩하기>를 참고해 주시면 좋겠다.

아일랜드는 1973년 EU에 가입하면서 외국인 직접투자가 실질적으로 증가하기 시작하였고 1990년 중반 이후부터 높은 성장을 이루어나갔다. 아래의 그래프에 나와 있는 것처럼 2021년에 아일랜드의 1인당 GDP는 10만 달러 수준에 육박하였다. 2021년 영국의 1인당 GDP는 46510달러로 아일랜드의 절반에 머무르고 있다. 아일랜드는 2001년부터 1인당 GDP 면에서 영국을 능가하기 시작하였다. 2001년 영국의 1인당 GDP는 27886달러, 아일랜드는 28282달러였다. 이 시기 이후 양국간 소득격차는 지속적으로 확대되었다. 1인당 GNI 및 그 성장률의 추세도 GDP의 그것과 매우 유사한 변화 패턴을 보여주고 있다.

아일랜드는 1987년 18.1%의 높은 실업률에 시달리던 나라였지만 1997년 사회파트너십 협약이 체결되면서 실업률이 지속적으로 낮아졌다. 기간마다 차이는 있지만, 아일랜드 2021년 현재 6.2%의 실업률을 보이고 있다. 외국인 직접투자 측면에서도 아일랜드는 성공적이다. 1990년 이전에 GDP 대비 외국인직접투자비율이 1% 미만에 불과하던 나라에서 2021년에는 16.1%를 나타내고 있어 외국인 직접투자 유치에 성공하다는 것을 보여준다. 이것은 아일랜드가 법인세 개혁, 노동시장 개혁 등을 통해 외국기업친화적인 경제환경을 마련한 덕분이기도 하다.

물론 2015년의 경우 처럼 GDP와 외국인직접투자가 빠르게 증가한 것을 두고 논란과 비판이 있다. 일례로 폴 크루그먼은 아일랜드가 2015년 GDP가 26.3% 급증한 것은 법인세 경쟁과 지식재산권 특례조항(Patent Box)을 이용해 만들어낸 환상과 같은 레프러콘 경제학(Leprechaun economics)이라고 비판한 것이 대표적이다.

그렇지만 유럽에 위치하고 있는 아일랜드는 경제적 측면에서 이미 克英을 달성한 것으로 보인다. <슬픈 아일랜드>의 저자 박지향 교수를 인터뷰한 배진영 기자는 인터뷰 기사에서 다음과 같이 지적한다. '물론 인구가 480만 명 남짓한 소국(小國)으로 외자에 대한 의존도가 높은 아일랜드 경제의 특성을 감안할 때, 아일랜드의 경제력을 과대평가해서는 곤란하다는 주장도 있다. 하지만 20세기 이후 독립한 나라 중에서 1인당 GDP에서 과거의 식민 모국을 추월한 나라는 싱가포르를 제외하면 아일랜드 뿐일 것이다.'

.

<아일랜드, 한국, 영국, 일본의 주요 경제지표> -> 표는 아래에 있습니다.

.

한편, 아시아에서는 일본의 식민지 경험이 있는 우리나라가 일본에 근접해 가고 있다. 유럽에 克英을 실현한 아일랜드가 있다면, 아시아에는 克日의 단계에 진입하고 있는 우리나라가 있다. 2021년 1인당 GDP 면에서 일본은 39312달러, 우리나라는 34997달러에 이르르고 있어 두 국가 간 소득격차가 그리 크지 않음을 보여준다.

아래의 그래프에서 알 수 있는 또 다른 사실은, 영국과 일본은 1인당 GDP 면에서 성장의 정체를 나타내고 있다는 것이다. 일본은 1995년 이후 소득이 일종의 박스권에서 변동하고 있다. 영국은 2004년도 4만 달러대를 찍은 이후 성장 정체를 경험하고 있다.

그렇지만, 아일랜드와 우리나라는 지속적인 소득 수준 향상을 보이고는 있다. 이 두 나라 사이에서도, 아일랜드는 여전히 높은 성장률을 보이고 있는 반면에 우리나라는 1980년대 후반부 이후 경제성장률이 지속적인 하락 추세에 있음을 보여준다. 성장과 관련된 스토리에는 나라마다 큰 차이가 있다. 우리의 경우 투입 요소의 확대가 어렵다면, 성장율을 높이기 위해 우선 경제 제도들이 효율을 높이는 방향으로 재구축되어야 한다.

한국인을 두고 '동양의 아일랜드인'이라고 하는 지적이 있는데, 일리가 있다는 생각이 든다. 강대한 이웃 옆에서 오랜 세월 이어온 수난의 역사, 그 과정에서 형성된 강한 민족의식, 뿌리 깊은 가난, 분단, 理性(이성)보다는 감정이 앞서는 민족성 등 면에서 그렇다.

서울대 박지향 교수는 또 지적한다. '아일랜드 과거 이야기와 우리의 이야기가 겹치는 장면들은 심금을 울리지만, 과거와 미래를 바라보는 시각에서 자기 폐쇄적인 면모를 떨쳐 버리고 있는 아일랜드의 현재 모습은 아직도 그러한 폐쇄성에 갇혀 있는 우리에게 좋은 지침이 될 것이다.' 우리나라도 이제 아일랜드가 경제적 克英을 통해 자신감을 회복했던 것처럼 우리도 빠른 성장을 통해 빨리 경제적인 克日을 이루기를 바란다.

로그인 또는 가입하여 보기

Facebook에서 게시물, 사진 등을 확인하세요.

www.facebook.com

아일랜드에 외국 투자가 많은 또 다른 이유

아일랜드 투자 광고

https://www.hankyung.com/international/article/2022080907371

'법인세 싼 나라' 아일랜드 1분기 성장률, 유로존 10배

'법인세 싼 나라' 아일랜드 1분기 성장률, 유로존 10배, 글로벌 기업 투자 대거 몰려 내년엔 최고세율 15%로 높여

www.hankyung.com

'지역별 자료 > 서부유럽' 카테고리의 다른 글

| CAN THE NORTH SEA BECOME EUROPE’S NEW ECONOMIC POWERHOUSE? (0) | 2023.01.07 |

|---|---|

| 북해(North Sea)는 석유 중심에서 풍력 단지로 빠르게 탈바꿈 중 (0) | 2023.01.07 |

| 유럽의 그린수소 파이프 논쟁 (그린수소냐 전기냐) (0) | 2022.12.26 |

| 곤경에 처한 프랑스 원전 (0) | 2022.12.18 |

| 프랑스 지방 살리기 위해 철도망 보강 필요 (Two-speed nation) (0) | 2022.12.18 |