추석 연휴 지나고 페이스북에 쓴 글을 옮겼습니다.

CAN JAPAN FEED ITSELF? (일본, 식량 자급 자족 가능?)

1. 1990년 이후 30년 넘게 매콤한 인플레이션 맛을 본적이 없음.

(특히 임금은 20년간 변함이 없는 지경)

2. 특히 서민들의 장바구니 물가에 민감하게 작용하는 식료품의 가격이 변동이 거의 없었는데, 그것은 바로 '세계화(Globalization)' 덕택에 값싸고 품질 좋은 식재료를 꾸준히 공급받을 수 있었기 때문임.

3. 최근 1년간 글로벌 공급망에 이상(러시아-우크라이나 전쟁으로 인한 원자재, 에너지, 비료, 식량 등 공급 차질) , 가뭄 같은 이상 기후, 엔화가치 하락으로 인해 식료품 가격이 치솟을 수 밖에 없었는데, 아직까지는 슈퍼마켓(유통) 분야에서 소비자에게 가격 전가를 아직 제대로 하지 않고 있어 다행(?)히도 아직까지 소비자들은 매콤한 인플레이션 맛을 보고 있지 않음. (일본 거주 중인 유튜버 박가네 영상을 보면 일본 대형 식료품 판매점의 박리다매 형태를 알 수 있음)

4. 하지만, 식료품 유통 분야도 소비자에게 가격 상승분을 떠넘기지 않으면 자기들이 죽을판. 20년간 소득이 증가하지 않는 가계의 곡소리는 이제부터 시작될 예정임. (한국은 슈퍼마켓 가서 '이거 가격 또 올랐네.. '를 쉽게 받아들이는데 일본은 전혀 그렇지 않다네요)

5. 특히 '식량 안보를 위해서는 특단의 조치가 필요하다' 라는데에는 공감하는데 앞을 가로 막는 장벽이 너무 높음. 특히 시골에선 젊은이들의 농업에 대한 혁신이 필요한데 시골의 할아버지 할머니에겐 혁신을 기대하기가 어려움.

6. 여기부턴, 벼농사만 주구장창하는 우리나라도 잘 들어봐야 할 얘기임.

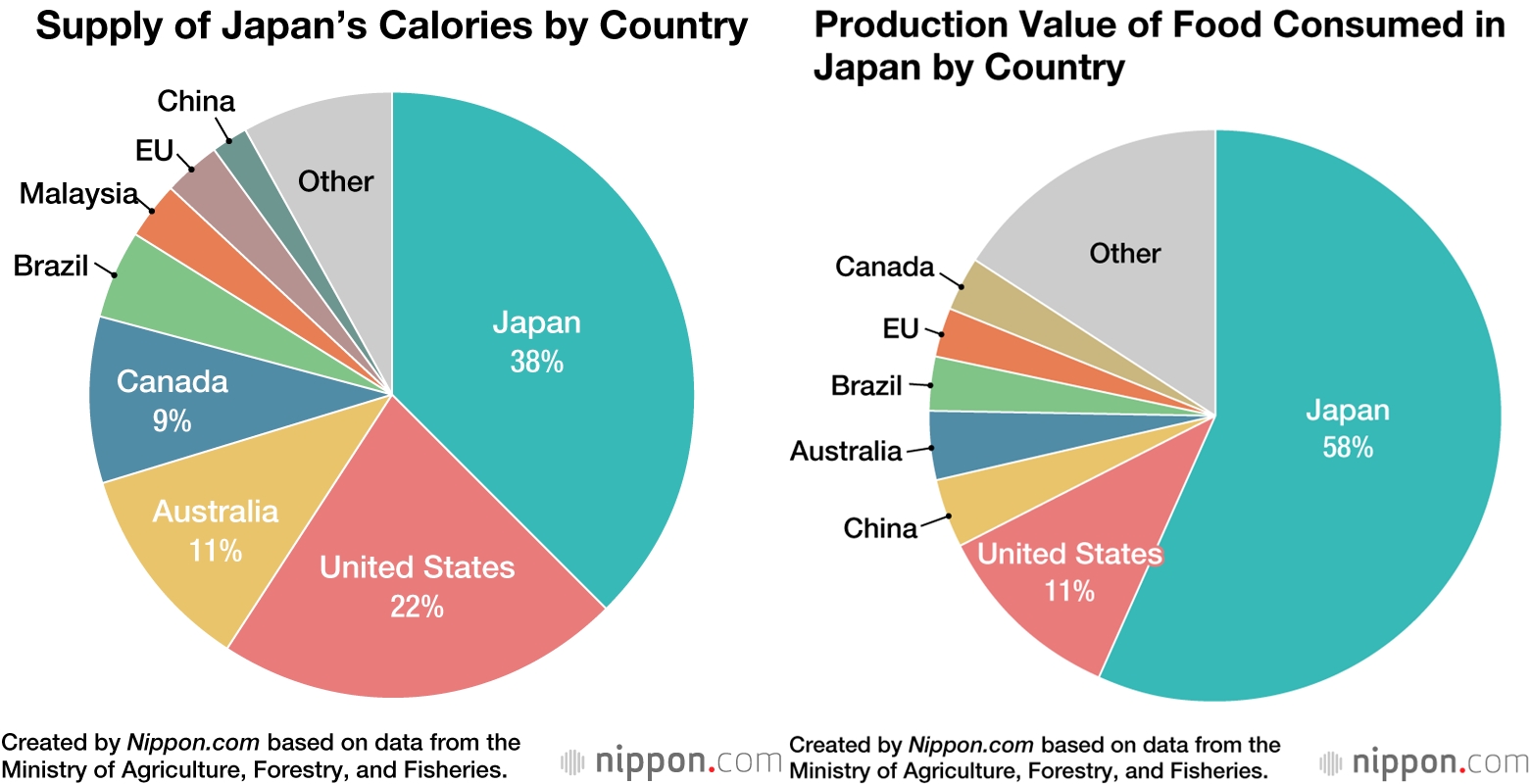

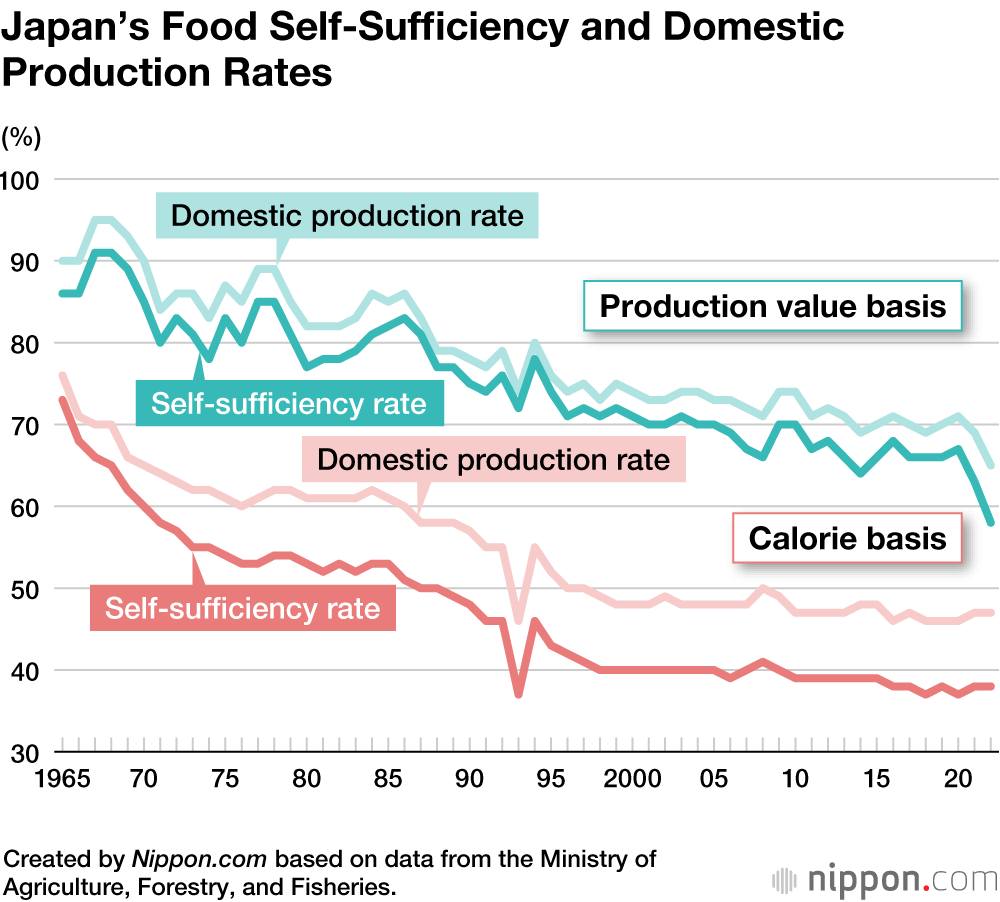

일본의 식량 자급률은 38%에 불과함. 식량 자급률을 분야별로 살펴보면 아래 그래프와 같음. 쌀은 거의 자급자족 상태인데 밀은 83%, 콩은 78%, 식용류는 97%가 수입이라니. 이게 뭔 개뼉다귀 같은 구성이란 말인가?

7. 원래 일본은 소득이 높은 경제적 신뢰도가 높은 국가이다보니 농업에 필수적인 칼륨, 인산염 등을 A국가, B국가 등 혹시 모를 사태에 대비해 수입선을 다변화해서 장기 계약으로 안정적으로 공급받았는데, 지금은 엔화는 가치가 떨어지지, 경제력은 약화일로이지, 게다가 중국의 등장으로 대량의 장기계약을 맺기가 어려워지고 있는 실정임. 중국은 훨씬 큰 구매력으로 장기 계약을 추진하려 하니 수출국 입장에서도 포트폴리오 구성할 때 중국은 기본값으로 두고 일본을 옵션으로 하려할테니 일본의 비료 공급도 과거에 비해 어려워질꺼란 얘기임.

8. 그래서 2022년 기시다 정부가 발표한 'New Capitalism' 프로그램을 보면 식량 자급률을 높이기 위해 농업을 부활시키고 젊은이들이 농업에 매력을 느낄 수 있도록 지원하는 여러 테크놀러지를 준비한다는 내용을 담았음. 근데, 정작 근본적이고 핵심 사안은 공급망이 무너져버린 혼돈속에서 비료를 어떻게 안정적으로 공급받느냐 임. 'No비료=No농업'. 그럼 일본에서 직접 비료 만들어? 그 얘긴, 요소수로 고생한 한국이 "야 이젠 요소수 수입하지 말고 국산화 해" 이 얘기하고 똑같음. 기술장벽이 높아서 못하는게 아니라 국산화하면 비용만 많이드니 안하는거지.

요약 : 중국에서 안정적으로 비료 공급 못 받으면 일본의 식량 자체 조달은 물 건너간 얘기.

9. 그럼 대안을 생각해보자. 신기술로 위기를 넘겨 볼까? Norinchukin(農林中央)라는 VC(벤쳐캐피탈)은 농업 기술 분야에 전문적인 투자를 하는데 로봇 손수레, 농장에 외국인 파견 온라인 프로그램 등을 개발하는데 큰 역할을 함. 이 회사로부터 투자를 받은 대표적인 회사가 Algal Bio (Algae는 적조, 녹조 할때 그 조류. 이걸 사료나 비료로 개발하는 회사)인데 얘네는 조류를 비료로 탈바꿈시키는 연구를 하고 있음. 이거 성공하면 비료 독립이 조금은 가까워짐. 그럼 식량 안보에도 큰 도움이 되겠죠? Algal Bio 대표이사는 에너지 독립을 위해서는 신재생에너지와 원자력의 도움도 생각해봐야한다고 주장함.

10. 모건 스탠리의 보고서를 통해 벼농사에 치우친 일본의 농업 구조에 대해 얘기해보자.

국내산 농산물 대비 수입산의 비율은 꾸준히 증가하고 있는데 오로지 관심은 쌀 100% 자급자족에 쏠려 있음. 게다가 정치적으로는 쌀 가격을 인위적으로 높게 유지시키려 노력함.

일본인의 연간 1인당 쌀 소비량은 118kg(1962년)에서 53.5kg(2018년)으로 감소했는데, 이런 변화에 일본 정부가 잘못 대응해서 일본의 식량 자급 자족이 어렵게 되었다고 주장한다.

벼농사 안지으면 인센티브를 주는 형태로 쌀 공급을 줄이고, 쌀 가격은 전세계에서 가장 높은 수준으로 인위적으로 유지시키는 방식은 독이 되었다고. 차라리 쌀의 100% 자급자족에 목메이지 말고 쌀 가격도 인위적으로 부양하지 말고 그냥 떨어지게 냅뒀더라면 쌀의 생산량은 자동으로 줄어들고 수요량은 좀 더 늘었을텐데 말이다. 그리고, 쌀이 아닌 국내산 밀가격을 인위적으로 높게 유지시켰더라면 밀농사에 보조금을 주었더라면 수입산 밀의 가격의 출렁임에도 조금은 더 안심되었을텐데 말이다. (여기에는 한가지 가정이 숨어 있다. 조금 더 비싸도 세계 최고의 품질을 자랑하는 자포니카 쌀을 사먹을 수요가 꽤나 있다라는 것을 가정하고 있다)

요약 : 쌀 품질은 꽤 좋아서 생각보다 경쟁력이 있어. 100% 자급자족에 목매이지 마. 보조금은 약한 고리인 밀에다 퍼부었으면 얼마나 좋았을까? 라고 얘기하고 있음.

PS

아직은 그래도 최악의 상황은 아님. 2007-2008때 보다 형편이 조금 낫긴 하지만...... 닥쳐올 파고는 더 높을 듯 하다.

Can Japan feed itself?

- Without immediate agricultural reforms, the country is vulnerable to an intensifying global food crisis

by Leo Lewis and Kana Inagaki in Tokyo SEPTEMBER 8 2022

At the end of the month, in supermarkets across Japan, regular staff and a secret army of wholesalers will work the shelves through the night on a project that none of them — from national chains to local stores — are able to talk about openly.

When the food retail industry’s collective doors open on October 1, shoppers who have barely experienced inflation since the early 1990s will be hit by the most severe price shock in almost two generations.

The prices of more than 6,000 daily food items will have soared overnight; so too, say experts whose warnings have long gone unheeded, will the Japanese public’s realisation of what it means to depend upon the most vulnerable food supply system in the developed world.

Japan’s high-quality, low self-sufficiency food system has always been a proxy for the march of globalisation. It could now become a proxy for its reversal.

The spectre of faltering food security, admit government officials, is a symbol of both the country’s decline as an economic superpower and the decaying norms of the globalised economic system that allowed Japan to thrive.

For the past year, Japan’s supermarket industry has shielded customers from a 48 per cent rise in import prices — much of that surge driven by the high cost of energy and, since March, the sustained collapse of the yen to a 24-year low against the dollar.

The choreographed effort to raise prices is in keeping with decades of habit in Japan’s fragmented and competitive supermarket industry — and in an economy that defined the phenomenon of deflation for the rest of the world. None would have felt comfortable acting on their own, particularly after more than 20 years where wages have stagnated. Now, however, unless businesses pass on the cost to consumers, they will struggle to survive.

There have been other shocks over the years, say officials, but this one feels different. Extreme weather, climate change and Covid-related disruption of logistics have highlighted the fragility of systems on which Japan has come to rely. By disrupting the global flows of food commodities, energy and chemical fertiliser, Russia’s war in Ukraine has laid bare the huge risks that Japan has, over decades, allowed to become structural within its food supply system.

If tensions between Taipei and Beijing escalate into a military conflict in the Taiwan Strait, disruption to this vital shipping route would be crippling for Japan’s food imports. Without immediate agricultural reforms, warns one of the country’s leading food experts, the sophisticated modern Japanese diet would be sent back to the rice and sweet potato Spartanism of the 1940s.

The Japanese government has acknowledged the darkening threat that now hangs over its food security: the question is whether it has the time, the incentives, the human resources and powers of innovation required to avert disaster.

“What’s different from the past is that Japan’s economic status has fallen. We need to think of [a new] strategy of supplying food to everyone now that the premise that Japan can buy whatever it likes from wherever in the world at any price is gone,” says Atsushi Suginaka, director-general for policy co-ordination at the ministry of agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

“The biggest problem facing agriculture is the lack of a willingness to take on new challenges. For an ageing population, it’s difficult to try something different and that’s why we need the participation of younger people.”

Geopolitical obstacles

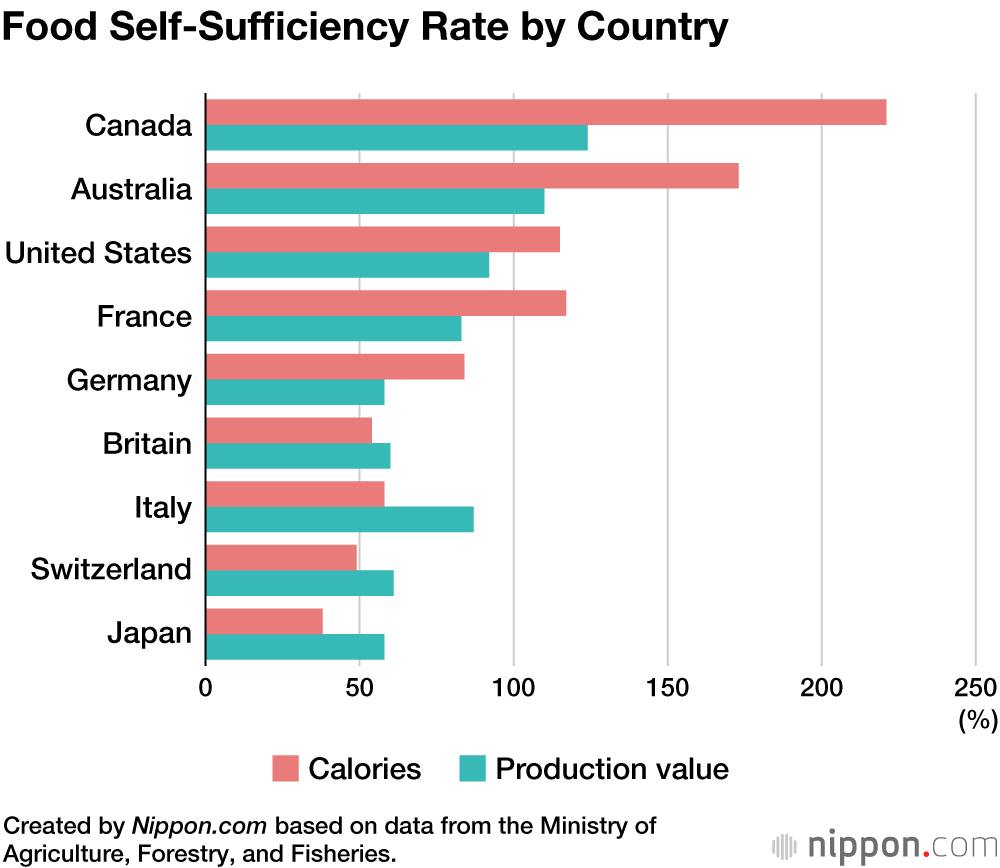

Though the October price increases are not enough to ruin Japanese households, they will provide an unambiguous reminder of the country’s food self-sufficiency rate of just 38 per cent, and its dependence on imports to make up the remaining calories consumed.

The self-sufficiency rate — now the lowest among major countries — has fallen from 73 per cent in 1965 as demand has risen for meat and other food it cannot produce on its own. Some of Japan’s dependencies, such as wheat (83 per cent imported), soyabeans (78 per cent) and edible oils (97 per cent) are exceptionally skewed.

The culinary scene Japan is famed for — from backstreet ramen noodle shops ranked by Michelin among the world’s finest restaurants, to the tempura udon dishes worshipped by traditionalists and specialist breads that triumph in international baking competitions — is almost entirely dependent on the outside world.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused upheaval in global food supplies as both countries are important grain exporters, between them accounting for almost a third of the world’s traded wheat. With supplies already tight, the situation could worsen if global crop yields also decline due to the shortage and high prices of fertilisers, where Japan’s import dependence is high at 75 per cent.

Even before the war, prices for key fertilisers jumped last year after the EU announced sanctions over human rights abuses against Belarus, a leading potash producer, and China and Russia, also large fertiliser exporters, put in place export curbs to safeguard domestic supply.

So far, Japan has navigated these geopolitical obstacles by securing deals with alternative suppliers such as Morocco and Canada for phosphate, potassium and other fertiliser ingredients. Over decades, the resource-poor country has carefully cultivated a sophisticated network of trading houses and economic partners as well as contingency plans so it can get hold of many of its imported foods even in cases of emergencies such as natural disasters and armed conflicts.

But even then, officials say, Japan’s sourcing ability will be severely limited if prices continue to rise, making it impossible to compete against China and other rivals with much bigger purchasing power.

Alarmed by the looming crisis, a group of parliamentarians from the ruling Liberal Democratic party in May submitted proposals for strengthening Japan’s food security. A month later, when Prime Minister Fumio Kishida unveiled a draft of his “new capitalism” programme, a section was devoted to outlining plans to revive the agricultural industry and deploy new technologies to make the sector more attractive to the younger generation.

“To establish food security in Japan, food self-sufficiency will be improved by creating robust agriculture, forestry and fisheries industries,” it read. As part of that effort, the government will aim to boost exports of agricultural, forestry and fishery products from ¥1.2tn last year to ¥5tn by 2030.

Still, some agricultural ministry officials say the Kishida administration has placed a bigger emphasis on economic security matters in areas such as semiconductor and battery technologies in the wake of the supply chain disruptions caused by Covid-19 and the risks exposed by the war in Ukraine. The same sense of urgency should be applied to food security, these officials say, especially since Japan retains internationally competitive technology in the breeding of rice, fruits and vegetables.

“Farming remains in Japan, and it is still highly regarded overseas. That’s not the case with semiconductor technology,” Suginaka says. “There is a risk that Japan will lose its development skills and would not be able to do farming if it cannot secure fertilisers from China. Then we would be in the same situation as chips. We must make sure that we do not lose our existing advantages.”

Homegrown solutions

With a succession crisis facing many of Japan’s ageing farmers, the prospects are grim for increasing domestic production of wheat and other agricultural products to reduce Japan’s dependency on imports. Instead, a key pillar of the Kishida administration’s food security agenda rests on the use of innovation and digital technologies to boost productivity and encourage younger people into the shrinking agricultural sector.

One example of this is the new venture capital arm of Norinchukin — an agricultural bank that has since 2019 established itself as an investor in a small selection of start-ups focused on agricultural technology. This ranges from robot wheelbarrows for elderly farmers to online systems for organising the dispatch of foreign workers to farms short of human staff.

Among the start-ups tackling Japan’s food crisis is Algal Bio, a University of Tokyo spin-off which is researching the use of algae as a supplement for animal protein to feed livestock or as fertilisers. The goal is to make the entire value chain for food products self-sufficient using algae that can be homegrown on almost any kind of land.

“The solutions for Japan’s energy crisis are clear. But when it comes to agriculture, that’s not the case,” says Amane Kimura, chief executive of Algal Bio, noting that the country can turn to nuclear power and renewable energy to reduce its reliance on imported energy.

In the case of agricultural products, however, simply increasing the volume of production is not necessarily the answer since Japan would still need to import fertilisers to grow the food. “There is an increasing sense of urgency for the need to create a new value chain for foods in order to genuinely raise the self-sufficiency rate,” Kimura adds.

Japan’s vulnerability to outside shock arises from a variety of factors that go beyond the country’s fundamental dependence on imports of energy and other critical resources.

The central crisis, argues Kazuhito Yamashita, a former agricultural ministry official and now research director at the Canon Institute for Global Studies, is that the long years of relatively crisis-free reliance on imports have permitted Japan to either overlook, or actively nurture, massive problems in domestic agriculture.

In common with the rest of the Japanese economy, the nation’s agriculture is placed at immediate risk by the ageing and shrinkage of the population. The countryside has experienced this particularly acutely, as its young have migrated to cities.

But even before they left and the average age of a Japanese farmer rose to 68, Japanese agriculture was inefficient and riddled with deep structural weaknesses and distortional incentives. The average size of Japanese farms, limited by a long history of prohibitively cumbersome legal baggage associated with the sale and consolidation of farmland, is extremely small. The national average is 3.1 hectares, but that average is significantly raised by the 30ha average in the northern island of Hokkaido.

Reform is vital, experts say, but there is currently little political momentum behind streamlining the sales of agricultural land to consolidators that could ultimately increase.

“Despite progress in agriculture reform, a much bigger crisis may be needed in order to trigger a response large enough to achieve the resilience and sustainability needed in the Japanese food supply chain,” said Morgan Stanley economist Robert Feldman.

Let them eat rice

In a recent study of the increasingly acute concerns around Japanese food security, Morgan Stanley analysts highlighted one of the key misconceptions that have provided both politicians and the general public with a false sense of security.

Despite the ever increasing ratio of imported to domestically produced food, Japan has historically remained politically committed to the idea that the nation should be 100 per cent self-sufficient in rice and that the price of domestic rice should remain artificially high.

That commitment, says Yamashita, has created some of the most dangerous distortions to Japan’s food supply, particularly as average rice consumption in Japan has fallen from a peak of 118kg a year in 1962 to 53.5kg in 2018.

In the face of that declining popularity, driven by the fact that the population is ageing and older people generally consume less food, the effort to maintain domestic rice at the highest price anyone in the world pays for the grain has created a system where owners of high quality farmland are incentivised not to grow rice and, therefore, squeeze supply.

“The Japanese government should have used a policy of allowing rice prices to fall in order to control its production and increase demand for rice while raising wheat prices to increase its production and control demand for wheat,” says Yamashita. “In reality, it implemented a policy that has achieved the exact opposite.”

The danger behind the dogma of rice self-sufficiency, say analysts, is that it has created a complacency whereby the threat of external shock on the food system is dismissed with the response, “Well, we will just eat more rice.”

Unfortunately, according to calculations by the investment bank Morgan Stanley, that is impossible. Wheat consumption in Japan, the bank said in a recent research paper, provides about 324 kcal a day per person and rice consumption about 519 kcal. If all of the wheat was replaced by rice, then rice production would have to rise by about 62 per cent.

There are two possible ways Japan could attempt to achieve this: either by finding extra paddy land or by raising the productivity of each hectare under rice cultivation. The implied additional demand of 4.8mn tonnes would require 900,000ha of new rice paddy cultivation. The government, meanwhile, estimates that the total of recoverable unused farmland in 2020 was 90,000ha.

Raising productivity would also be a non-starter, analysts say. Between 2000 and 2020 output per hectare grew by 0.184 per cent a year on average. At this pace, according to Morgan Stanley’s research, increasing output per acre by 62 per cent would take 262 years.

Meanwhile, the threat of external shock rises. “Japan has some very bad neighbours: North Korea, China and Russia. We could have a food crisis if there is some sort of incident in the Taiwan Strait and the imports of food are disrupted,” adds Yamashita, who argues that the Japanese government’s obsession with maintaining high rice prices made a mockery of its stated new concerns regarding food security.

For too long, Japan had underestimated its food security risks, says Akio Shibata, president of the Natural Resource Research Institute. Similar to how the country’s manufacturers expanded by building plants worldwide, its food strategy was also based on the pursuit of economic efficiency and global trade — which in turn was a symbol of Japan’s status as a global economic power.

“The reality now is that Japan can no longer get hold of food or energy resources at reasonable prices, and it needs to reverse its strategy of depending so heavily on the outside world,” Shibata said. “There were signs of strain from before, but Japan had not taken action thinking it was a temporary phenomenon. Now it may be too late to reverse course.”

일본은 스스로 식량을 조달할 수 있을까요?

- 즉각적인 농업 개혁이 없다면 일본은 심화되는 글로벌 식량 위기에 취약합니다.

by 레오 루이스, 도쿄의 카나 이나가키 2022년 9월 8일

이달 말, 일본 전역의 슈퍼마켓에서 정규 직원과 비밀 도매업자들이 전국 체인점부터 지역 상점에 이르기까지 그 누구도 공개적으로 이야기할 수 없는 프로젝트를 위해 밤새 진열대에서 일할 것입니다.

10월 1일 식품 소매업계가 일제히 문을 열면 1990년대 초반 이후 인플레이션을 거의 경험하지 못한 쇼핑객들은 거의 두 세대 만에 가장 심각한 가격 충격에 시달리게 될 것입니다.

하룻밤 사이에 6,000개 이상의 식료품 가격이 치솟을 것이며, 오랫동안 경고에 귀 기울이지 않았던 전문가들도 선진국에서 가장 취약한 식량 공급 시스템에 의존하는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지 일본 국민들이 깨닫게 될 것이라고 말합니다.

일본의 고품질, 낮은 자급률의 식량 시스템은 항상 세계화의 행진에 대한 대리인 역할을 해왔습니다. 이제 그 역전의 대리인이 될 수도 있습니다.

정부 관리들은 식량 안보가 흔들리고 있다는 유령은 경제 대국으로서 일본의 쇠퇴와 일본이 번영할 수 있었던 세계화 경제 시스템의 규범이 붕괴되고 있다는 상징이라고 인정합니다.

지난 한 해 동안 일본의 슈퍼마켓 업계는 높은 에너지 비용과 3월 이후 달러 대비 엔화가 24년 만에 최저치로 폭락하면서 수입 물가가 48%나 급등하는 것을 막아냈습니다.

일본의 세분화되고 경쟁이 치열한 슈퍼마켓 업계에서 수십 년 동안 이어져 온 관행과 전 세계에 디플레이션 현상을 불러일으킨 경제 상황을 고려할 때, 조직적인 가격 인상 노력은 당연한 결과입니다. 특히 임금이 정체된 20년이 넘는 기간 동안에는 누구도 스스로 행동하는 것이 편하다고 느끼지 않았을 것입니다. 하지만 이제는 기업이 비용을 소비자에게 전가하지 않으면 생존에 어려움을 겪을 것입니다.

관계자들은 지난 몇 년 동안 다른 충격도 있었지만 이번 충격은 다르게 느껴진다고 말합니다. 극심한 날씨, 기후 변화, 코로나로 인한 물류 차질은 일본이 의존해 온 시스템의 취약성을 부각시켰습니다. 러시아의 우크라이나 전쟁은 식량, 에너지, 화학 비료의 글로벌 흐름을 방해함으로써 수십 년 동안 일본이 식량 공급 시스템 내에서 구조적으로 허용해 온 엄청난 위험을 드러냈습니다.

타이베이와 베이징 사이의 긴장이 대만 해협에서 군사적 충돌로 확대되면 이 중요한 운송 경로가 중단되어 일본의 식량 수입에 큰 타격을 입게 될 것입니다. 일본 최고의 식품 전문가 중 한 명은 즉각적인 농업 개혁이 없다면 정교한 현대 일본 식단은 1940년대의 쌀과 고구마 스파르타주의로 되돌아갈 것이라고 경고합니다.

일본 정부는 현재 식량 안보에 대한 어두운 위협을 인정했습니다. 문제는 재앙을 피하는 데 필요한 시간, 인센티브, 인적 자원 및 혁신의 힘이 있는지에 대한 것입니다.

"과거와 다른 점은 일본의 경제적 지위가 떨어졌다는 것입니다. 일본이 세계 어디에서든 원하는 식량을 원하는 가격에 구입할 수 있다는 전제가 사라진 지금, 모든 사람에게 식량을 공급하기 위한 새로운 전략을 생각해야 합니다."라고 농림수산성 정책조정국장 아츠시 스기나카(Atsushi Suginaka)는 말합니다.

"농업이 직면한 가장 큰 문제는 새로운 도전에 대한 의지가 부족하다는 것입니다. 인구가 고령화되면 새로운 시도를 하기가 어렵기 때문에 젊은 사람들의 참여가 필요합니다."

지정학적 장애물

10월의 물가 인상이 일본 가계를 파탄낼 정도는 아니지만, 38%에 불과한 일본의 식량 자급률과 나머지 칼로리를 보충하기 위해 수입에 의존하고 있다는 사실을 분명하게 상기시켜줄 것입니다.

현재 주요 국가 중 가장 낮은 식량 자급률은 1965년 73%에서 자체 생산이 불가능한 육류 및 기타 식품에 대한 수요가 증가함에 따라 하락했습니다. 밀(83% 수입), 대두(78%), 식용유(97%)와 같은 일부 품목의 수입 의존도는 매우 왜곡되어 있습니다.

미슐랭이 세계 최고의 레스토랑으로 선정한 뒷골목 라멘 가게부터 전통주의자들이 숭배하는 튀김 우동 요리, 국제 제빵 대회에서 우승하는 전문 빵에 이르기까지 일본이 자랑하는 요리는 거의 전적으로 외부 세계에 의존하고 있습니다.

러시아의 우크라이나 침공은 전 세계 밀 교역량의 거의 3분의 1을 차지하는 두 나라의 중요한 곡물 수출국으로서 세계 식량 공급에 격변을 일으켰습니다. 이미 공급이 부족한 상황에서 일본의 수입 의존도가 75%로 높은 비료의 부족과 높은 가격으로 인해 전 세계 작물 수확량까지 감소하면 상황은 더욱 악화될 수 있습니다.

전쟁이 일어나기 전인 지난해에도 유럽연합이 주요 칼륨 생산국인 벨라루스에 대한 인권 침해 제재를 발표하고, 대규모 비료 수출국인 중국과 러시아가 국내 공급을 보호하기 위해 수출 제한 조치를 취한 후 주요 비료 가격이 급등했습니다.

지금까지 일본은 인산염, 칼륨 및 기타 비료 성분에 대해 모로코 및 캐나다와 같은 대체 공급업체와 거래를 확보함으로써 이러한 지정학적 장애물을 극복해 왔습니다. 자원이 부족한 이 나라는 수십 년에 걸쳐 정교한 무역업체 및 경제 파트너 네트워크와 비상 계획을 세심하게 구축하여 자연재해나 무력 분쟁과 같은 비상 상황에서도 많은 수입 식량을 확보할 수 있도록 했습니다.

그러나 관리들은 그럼에도 불구하고 가격이 계속 상승하면 일본의 소싱 능력이 심각하게 제한되어 중국 및 훨씬 더 큰 구매력을 가진 다른 라이벌과 경쟁 할 수 없게 될 것이라고 말합니다.

다가오는 위기에 경각심을 느낀 집권 자민당 의원들은 지난 5월 일본의 식량 안보를 강화하기 위한 제안을 제출했습니다. 한 달 후, 기시다 후미오 총리가 '신자본주의' 프로그램 초안을 발표하면서 농업 산업을 부흥시키고 젊은 세대에게 더 매력적인 산업으로 만들기 위해 새로운 기술을 도입할 계획을 설명하는 섹션이 포함되었습니다.

"일본의 식량 안보를 확립하기 위해 강력한 농림수산업을 육성하여 식량 자급률을 향상시킬 것입니다."라고 적혀 있습니다. 이러한 노력의 일환으로 정부는 농림수산물 수출을 지난해 1조 2천억 엔에서 2030년까지 5조 엔으로 늘리는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다.

하지만 일부 농업부 관리들은 기시다 정부가 코로나19로 인한 공급망 붕괴와 우크라이나 전쟁으로 인한 위험 노출로 반도체 및 배터리 기술과 같은 분야의 경제 안보 문제에 더 중점을 두고 있다고 말합니다. 특히 일본은 쌀, 과일, 채소 육종 분야에서 국제적으로 경쟁력 있는 기술을 보유하고 있기 때문에 식량 안보에도 같은 긴박감을 적용해야 한다고 이 관리들은 말합니다.

"농업은 일본에 남아 있고 해외에서도 여전히 높은 평가를 받고 있습니다. 반도체 기술은 그렇지 않습니다."라고 스기나카는 말합니다. "중국에서 비료를 확보하지 못하면 일본이 개발 기술을 잃고 농사를 지을 수 없게 될 위험이 있습니다. 그러면 우리도 칩과 같은 상황에 처하게 될 것입니다. 기존의 장점을 잃지 않도록 해야 합니다."

자체 개발 솔루션

일본의 많은 고령 농부들이 승계 위기에 직면해 있는 상황에서 밀과 기타 농산물의 국내 생산을 늘려 일본의 수입 의존도를 낮출 수 있을지에 대한 전망은 어둡습니다. 대신 기시다 정부의 식량 안보 의제의 핵심 축은 혁신과 디지털 기술을 활용해 생산성을 높이고 젊은이들이 위축된 농업 부문에 뛰어들도록 장려하는 데 있습니다.

2019년부터 농업 기술에 중점을 둔 소수의 스타트업에 대한 투자자로 자리매김한 농업 은행인 노린추킨의 새로운 벤처 캐피탈 부서가 그 예입니다. 여기에는 고령 농부를 위한 로봇 손수레부터 일손이 부족한 농가에 외국인 노동자를 파견하는 온라인 시스템까지 다양합니다.

일본의 식량 위기에 대처하는 스타트업 중에는 도쿄대학에서 분사하여 가축의 사료나 비료로 동물성 단백질 보충제로 해조류를 사용하는 방법을 연구하는 Algal Bio가 있습니다. 거의 모든 종류의 땅에서 자생할 수 있는 해조류를 이용해 식료품의 전체 가치 사슬을 자급자족하는 것이 목표입니다.

"일본의 에너지 위기에 대한 해결책은 분명합니다. 하지만 농업 분야에서는 그렇지 않습니다."라고 Algal Bio의 최고 경영자인 아마네 기무라는 원자력 및 재생 에너지로 전환하여 수입 에너지 의존도를 낮출 수 있다고 지적합니다.

그러나 농산물의 경우 일본이 식량을 재배하기 위해 여전히 비료를 수입해야 하기 때문에 단순히 생산량을 늘리는 것이 반드시 정답은 아닙니다. 기무라는 "진정한 식량 자급률을 높이기 위해서는 새로운 식량 가치 사슬을 만들어야 한다는 절박감이 커지고 있다"고 덧붙입니다.

외부 충격에 대한 일본의 취약성은 에너지 및 기타 주요 자원의 수입에 대한 일본의 근본적인 의존도를 넘어서는 다양한 요인에서 비롯됩니다.

전직 농업부 관리이자 현재 캐논 글로벌 연구소의 연구 책임자인 야마시타 카즈히토는 일본이 오랜 기간 동안 상대적으로 위기 없이 수입에 의존해 왔기 때문에 국내 농업의 거대한 문제를 간과하거나 적극적으로 육성할 수 있었다는 것이 가장 큰 위기라고 주장합니다.

다른 일본 경제와 마찬가지로 일본 농업은 고령화와 인구 감소로 인해 즉각적인 위험에 처해 있습니다. 특히 시골은 젊은이들이 도시로 이주하면서 이러한 문제를 더욱 심각하게 경험하고 있습니다.

그러나 이들이 도시로 떠나고 일본 농가의 평균 연령이 68세로 높아지기 전에도 일본 농업은 비효율적이었고 구조적 약점과 왜곡된 인센티브로 가득 차 있었습니다. 일본 농장의 평균 규모는 농지 판매 및 통합과 관련된 엄청나게 번거로운 법적 짐의 오랜 역사에 의해 제한되어 극히 작습니다. 전국 평균은 3.1헥타르이지만, 홋카이도 북부의 평균 30헥타르에 비하면 이 수치는 상당히 높습니다.

전문가들은 개혁이 필수적이지만 현재 농지를 통합업체에 판매하는 것을 간소화하여 궁극적으로 늘릴 수 있는 정치적 동력이 거의 없다고 말합니다.

모건 스탠리의 경제학자 로버트 펠드먼은 "농업 개혁의 진전에도 불구하고 일본 식품 공급망에 필요한 회복력과 지속 가능성을 달성할 수 있을 만큼 큰 규모의 대응을 촉발하기 위해서는 훨씬 더 큰 위기가 필요할 수 있습니다."라고 말했습니다.

쌀을 먹게 하자

모건 스탠리 애널리스트들은 최근 일본의 식량 안보에 대한 우려가 점점 더 심각해지고 있는 상황에서 정치인과 일반 대중 모두에게 잘못된 안보 의식을 심어준 주요 오해 중 하나를 강조했습니다.

수입 식품과 국내 생산 식품의 비율이 계속 증가하고 있음에도 불구하고 일본은 역사적으로 쌀을 100% 자급자족하고 국내 쌀 가격을 인위적으로 높게 유지해야 한다는 생각에 정치적으로 전념해 왔습니다.

야마시타는 일본의 평균 쌀 소비량이 1962년 연간 118kg으로 정점을 찍은 후 2018년에는 53.5kg으로 감소하는 등 이러한 노력이 일본의 식량 공급에 가장 위험한 왜곡을 초래했다고 말합니다.

인구 고령화와 노년층의 식품 소비량 감소로 인해 쌀 소비량이 감소하고 있는 상황에서, 일본 정부가 국내산 쌀을 세계에서 가장 높은 가격으로 유지하려는 노력은 고품질 농지 소유주들이 쌀을 재배하지 않도록 인센티브를 부여하여 공급을 압박하는 시스템을 만들었습니다.

야마시타는 "일본 정부는 쌀 생산을 조절하고 쌀 수요를 늘리기 위해 쌀 가격을 떨어뜨리고 밀 생산을 늘리고 밀 수요를 조절하기 위해 밀 가격을 올리는 정책을 사용했어야 합니다."라고 말합니다. "실제로는 정반대의 결과를 가져온 정책을 시행했습니다."

분석가들은 쌀 자급자족이라는 도그마의 이면에 있는 위험은 식량 시스템에 대한 외부 충격의 위협을 "쌀을 더 많이 먹으면 되겠지"라는 반응으로 무시하는 안일함을 만들어냈다는 점이라고 말합니다.

안타깝게도 투자은행 모건 스탠리의 계산에 따르면 이는 불가능합니다. 이 은행은 최근 연구 논문에서 일본의 밀 소비량은 1인당 하루에 약 324kcal, 쌀 소비량은 약 519kcal를 제공한다고 밝혔습니다. 밀을 모두 쌀로 대체한다면 쌀 생산량은 약 62퍼센트 증가해야 합니다.

일본이 이를 달성하기 위해 시도할 수 있는 두 가지 방법은 논을 추가로 확보하거나 벼 재배 헥타르당 생산성을 높이는 것입니다. 480만 톤의 추가 수요를 달성하려면 90만ha의 논을 새로 경작해야 합니다. 한편 정부는 2020년에 회수 가능한 유휴 농지가 총 9만ha에 달할 것으로 추정하고 있습니다.

분석가들은 생산성을 높이는 것 또한 시작이 아니라고 말합니다. 2000년부터 2020년까지 헥타르당 생산량은 연평균 0.184퍼센트씩 증가했습니다. 모건 스탠리의 연구에 따르면 이 속도로 에이커당 생산량을 62% 늘리려면 262년이 걸릴 것으로 예상됩니다.

한편 외부 충격의 위협도 커지고 있습니다. "일본에는 매우 나쁜 이웃이 있습니다: 북한, 중국, 러시아. 대만 해협에서 어떤 사건이 발생해 식량 수입에 차질이 생기면 식량 위기가 올 수 있습니다." 야마시타는 높은 쌀값 유지에 집착하는 일본 정부가 식량 안보에 대한 새로운 우려를 조롱하고 있다고 주장합니다.

천연자원연구소의 시바타 아키오 소장은 일본이 너무 오랫동안 식량 안보 위험을 과소평가했다고 말합니다. 일본 제조업체들이 전 세계에 공장을 건설하여 사업을 확장한 것과 마찬가지로 일본의 식량 전략도 경제적 효율성과 글로벌 무역을 추구했으며, 이는 글로벌 경제 강국으로서의 일본의 위상을 상징하는 것이었습니다.

시바타는 "이제 일본은 더 이상 합리적인 가격으로 식량이나 에너지 자원을 확보할 수 없는 것이 현실이며, 외부 세계에 지나치게 의존하는 전략을 바꿔야 합니다."라고 말합니다. "이전부터 긴장의 징후가 있었지만 일본은 일시적인 현상이라고 생각하고 조치를 취하지 않았습니다. 이제 방향을 바꾸기에는 너무 늦었을 수 있습니다."

Can Japan feed itself?

Without immediate agricultural reforms, the country is vulnerable to an intensifying global food crisis

www.ft.com

'지역별 자료 > 아시아(한,중,일)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 대만 주변 군사지도 (0) | 2022.11.30 |

|---|---|

| FORTRESS CHINA (시진핑의 내수화 전략) (0) | 2022.10.10 |

| 중국의 밭농사 vs 벼농사 지도 (0) | 2022.07.18 |

| 중국의 신재생에너지 (0) | 2022.06.26 |

| 중국 대운하 (0) | 2022.05.17 |