Putin’s Food Security Agenda

Under Vladimir Putin, “food problems” (prodovol’stvennye problemy) were once again elevated as a central concern of the state. The sad state of Russian livestock herds reappeared as a political issue: “we are particularly concerned about the situation in livestock production,” noted Alexey Gordeev, minister of agriculture in 2007. Like Soviet leaders in generations past, Putin saw the need to address both the production and consumption sides of these problems. Over the first two decades of his presidency, the Russian government developed a full-fledged rural recovery program, known as the food security or food sovereignty agenda. Agricultural policies during these years aligned with a broader shift toward economic nationalism and the strengthening of state capitalism, which were tied up with Putin’s political project of strengthening the state and its control of natural resources. A cornucopia of evolving policy interventions have served the goal of reviving domestic agriculture: trade restrictions, a variety of subsidies and subsidized credits, local content rules, simplified and lower tax regimes, and newly created state-owned banks and other enterprises, outlined in more detail below. The first program for rural recovery, adopted in 2000, was known as the Basic Directions of Agrifood Policy. Initially hamstrung by a tight budget, as oil prices rose and tax collection improved in the middle of the first decade of the new millennium, state support for domestic agriculture strengthened. By around 2005, several programs had been established under the umbrella of the National Priority Project: Development of the Agro-food Complex (2005). Between 2005 and 2010, total state support for agriculture more than tripled in nominal rubles, rising by 135 percent in real rubles. Sustained public support and trade protection have brought more meat to Russian tables and helped boost grain exports. By 2010, wheat—Russia’s most important crop, grown on 22 percent of arable land—had once again became an important export commodity. Figure 1.2 shows an export terminal for Russian grain in Rostov in 2012.

The Russian government’s most high-profile policy initiative was the National Food Security Doctrine, first published as a draft in 2008 and adopted in 2010. As noted earlier in this chapter, in contemporary Russia, food security is largely seen as a question to be addressed at the level of the national economy. Food insecurity is not primarily seen as a problem affecting individuals (the more common interpretation of this term) but as a threat emanating from politically motivated foreign actors cutting off the sale of food commodities to Russia. In this interpretation, food security is a sovereignty problem, and the two terms are in fact often conflated. The centerpiece of the Food Security Doctrine was a set of precise and ambitious self-sufficiency targets for staples of the Russian diet. These goals were to be realized through support to producers in targeted subsectors. The doctrine was in many ways a response to the failure of Boris Yeltsin’s reforms. Yeltsin had intended to reshape rural property relations and modernize agriculture, but reforms of the nineties did not actually center on food provision. Like Soviet leaders before him, Yeltsin sought to respond to the failures of Gorbachev’s reforms, which he perceived as too slow and too timid. At the same time, Yeltsin was deeply influenced by the international economic policy consensus at the time that considered the state to be the source of inefficiencies, and market forces the solution. The ideational core of the reforms in the 1990s was market liberalization; the “food problem” should be left to the markets, not the state. Vladimir Putin, in turn, responded to the problems of the newly privatized but utterly failing collective farms he inherited from the Yeltsin year. He rejected the Yeltsin-era embrace of “market fundamentalism” that had, in his eyes, undermined the legitimacy of the state and greatly weakened Russia internationally. Putin-era rural recovery plans were food policies as much as they were agricultural policies.

The Food Security Doctrine had both domestic and foreign policy goals, each reflecting past experiences and current opportunities. On the domestic side of the equation, price stability for basic staple foods was one of the main aims. This was a direct response to hyperinflation, output collapse, and skyrocketing prices of staple foods in the nineties, which had led to widespread hardship that had undermined Yeltsin’s legitimacy. Food security was about guaranteeing that citizens had access to a minimum of affordable staples, and this was to be achieved via the state-supported expansion of domestically produced food and occasional price ceilings on retail prices. The Putin government repeatedly adopted measures to control retail prices for basic “socially important” food commodities, such as wheat, sugar, and oils; this happened in 2010, a drought year, and in 2021, an election year, for example. Food retail prices were controlled through a freeze agreed upon by the Russian Federal Tariff Service, the industry association, and the country’s major retail chains. “We will not allow any surges in grain or food prices,” declared Aleksey Gordeev in response to less-than-expected wheat yields in 2012, for example. The government also went back to a Soviet-era practice of setting “rational norms of consumption” (ratsional’naya norma potrebleniia) that were then translated into production targets. For meat, the Food Security Doctrine set the norm at a relatively high seventy-five kilograms per person per year.

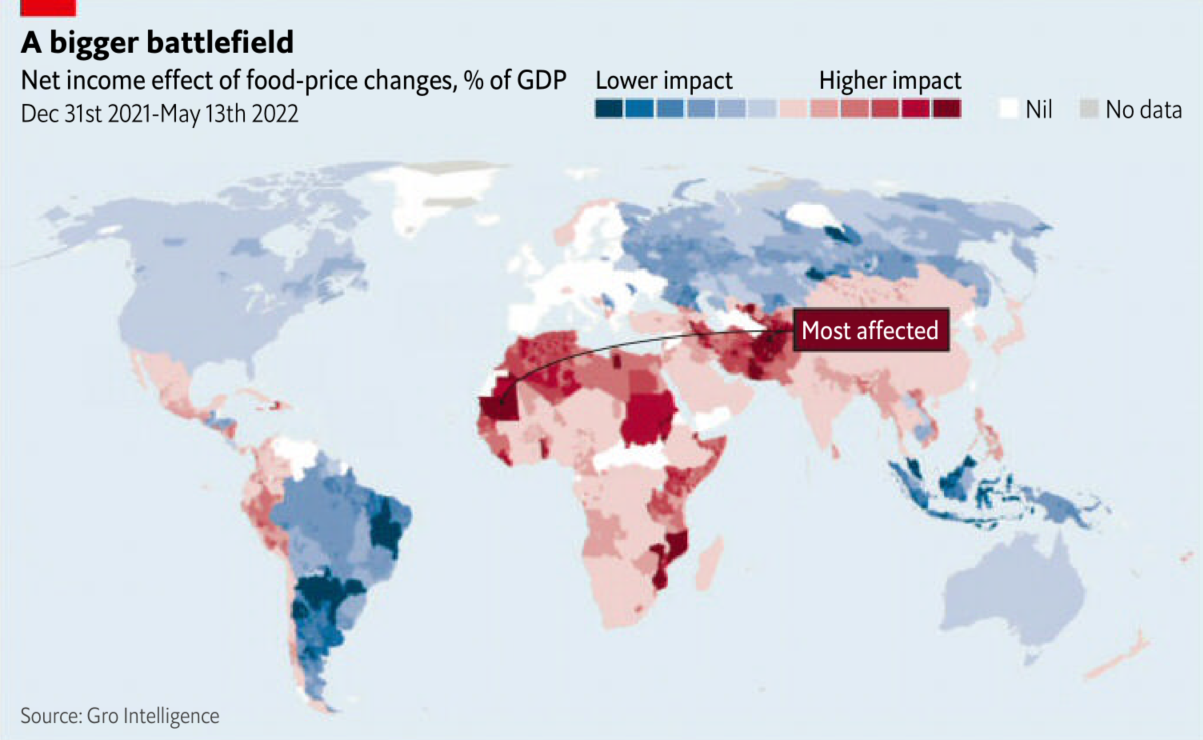

At the same time, food security and food sovereignty were also elements of Russian foreign policy that were explicitly coordinated with the country’s national security policy. Russia had inherited its dependence on foreign food imports from the Soviet Union, but the crisis of the nineties broadened and deepened the range of food imports. When Putin became president, he essentially declared this kind of deep market integration in food commodities a threat to Russian sovereignty. A sharp increase in global food commodity prices across the world between 2005 and 2008 also contributed to rising concerns. Putin’s agriculture policies held out a greater degree of food commodity autarky as a desirable policy goal—a sharp break indeed from free trade and the globalization of food commodity markets that dominated the Yeltsin agenda. Russia still imported food, but the Food Security Doctrine defined self-sufficiency targets for the basic staples of the Russian diet. For example, Russia was to supply itself with 95 percent of the required grain and potatoes; 95 percent of milk and dairy products; 85 percent of salt, meat, and meat products; and 80 percent of sugar, vegetable oil, and fish products. These were political goals, providing metrics to measure success in attaining food security. When Russian wheat exports not only recovered but also gained global market shares after 2010, Russia went further and started to promote the possibility of influencing global affairs via global grain prices—that is, to use grain exports as a foreign policy tool. Gordeev boasted that Russia has become a “major agrarian power” in 2008. Government officials even floated the idea of a global wheat cartel modeled on OPEC. This vision was never realized as it relied on close cooperation with Ukraine. In less zero-sum terms, Russian commentators framed Russia’s wheat bonanza as a contribution to feeding a growing world population. More concretely, the relations between Russia and a number of countries that are major importers of Russian grain—Turkey, Syria, Egypt, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Pakistan—strengthened. Map 1.2. shows the main export destinations for Russian wheat, illustrating the truly global reach of the country’s most important field crop.

While firmly rooted and embedded in domestic realities, the food sovereignty agenda was also a response to the increasing availability of foreign and domestic capital for rural investment. Although many factors contributed to the failures of Yeltsin’s land privatization, in retrospect, one of the most important differences between the nineties and the new millennium was the scarcity of capital in the former period and its availability in the latter. For a number of reasons addressed in detail in the next chapter, domestic oligarchs and international investors took an interest in Russian farmland starting in the early twenty-first century. The Putin government in turn realized that Russia’s arable land was an attractive investment opportunity for global and domestic investors and actively sought to enlist them for his political goals. Note an interesting paradox here: the food security agenda was essentially an economic nationalist agenda, aimed at reducing dependence on foreign food. Yet the Putin government was not at all hesitant to rely on both domestic and foreign capital to achieve this goal (although the share of foreign capital declined after 2014). Various policy tools and an evolving series of programs fostered the growth of a new type of private actor in the Russian countryside, the large corporate agricultural operators known as agroholdings. Putin referred to these policies as “market instruments,” deployed to “react to international markets.” Much to the frustration of Western observers who wanted to see a commitment to market mechanisms, markets were seen as a means, not an end in themselves.

As had been true during the Soviet era, now three types of agricultural policies were key. The first type comprised subsidies, or policies related to the costs and rewards of farming. The second type consisted of policies related to land use, and the third was made up of trade policies. While rural reforms initially paid lip service to and afforded a degree of rhetorical support for small-scale farming, by 2010, Putin’s economic team had largely abandoned Yeltsin’s notion of supporting small farms. In part, this followed from the reality that only a few kolkhozniki had pursued private farming. More than that, however, it was a reflection of a belief that large farms were better able to achieve the political goals they set out to accomplish. Putin and successive agricultural ministers, Alexey Gordeev and Alexander Tkachov, were firmly convinced that “large farms were necessary to provide food security of the country.” As we will see, Putin’s agenda entailed a very particular relationship between the state and agroholdings. One company will repeatedly appear as an example of this special relationship—EkoNiva. The company was founded in 1994 by Stefan Dürr, a German entrepreneur who had gone to the Soviet Union as a student and became an intern on Soviet farms in Moscow and Kursk. Dürr stayed in Russia and founded EkoNiva as a farm that grew organic buckwheat and imported Western agricultural machinery and seeds. Today, EkoNiva is the country’s largest milk producer and is known as Russia’s Milk Empire. A large, vertically integrated dairy producer, with dairy and crop farms across European Russia and Siberia, in 2020 the company was operating production facilities in Voronezh, Kursk, Leningrad, Moscow, Kaluga, Orenburg, Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, Tyumen, Novosibirsk, and Altai.

'지역별 자료 > 러시아,동유럽' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 국가별 우크라이나 밀(wheat) 의존도 (0) | 2022.03.10 |

|---|---|

| 유럽의 LNG (탈 러시아 대비) (0) | 2022.03.06 |

| 우크라이나 침공에 대한 서방의 경제 제재를 러시아는 버틸 수 있을까? (0) | 2022.02.23 |

| 구 소련의 농업 지도 (0) | 2022.02.21 |

| 유럽의 천연가스 러시아 의존도 (0) | 2022.02.20 |